Pages

1

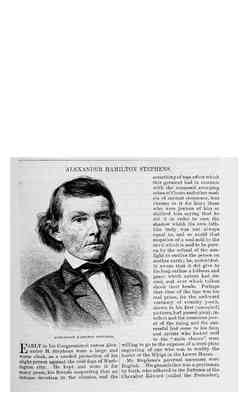

Alexander Hamilton Stephens

Early in his congressional career Alexander H. Stephens wore a large and warm cloak, as a needed protection of his slight person against cold fogs of Washington city. He kept and wore it for many years, his friends suspecting that an intense devotion to the classics, and the something of toga effect which this garment had in common with the supposed sweeping robes of Cicero and other models of ancient eloquence, lent charms to it for him; those who were jealous of him or disliked him saying that he did it in order to cast the shadpw which his own lathlike body was not always equal to, and so avoid that suspiscion of a soul sold to the devil which is said to be proven by the refusal of the sunlight to outline the person on mother eath; he, undoubtedly aware that it did give to his long outline a fullness and grace which nature had denied, and over which tailors shook their heads. Perhaps that time of the toga was his real prime, for the awkward verdancy of country youth, shown in his first (uncopied) pictures, had passed away, intellect and the consious power of the rising and the successful had come to his face, and artists who looked well to the "main chance" were willing to go to the expense of a steel -plate engraving of one who was in reality the leader of the Whigs in the Lower House. Mr. Stephens's paternal ancestors were English. His grandfather was a gentleman by birth, who adhered to the fortunes of the Chevalier Edward (called the Pretender),

2

[388 Harper's New Monthly Magazine]

and was therefore opposed to the house of Hanover, of which his Majesty George III. was the representative at the time of our war of Revolution. This ancestor of his came to America during some of the many Indian troubles and the contests with the French that preceded the seperation of the colonies from Great Britian, and served under General Braddock while marching on Fort Duquesne. He shared in the memorable defeat and retreat. In another expedition he served under Colonel (afterward General and President) Washington. During the war for independence this first of American Stephenses took an active part on the side of the revolted colonies with more ethusiasm than that with which his grandsom espoused the rebellion of 1861, and arose to the rank of captain on the patriot side. His home was then in Pennsylvania. In the year 1795 he sttled lands in Georgia, first in what is now Elbert County, then in Wilkes County, on Kettle Creek, where he dwelt until 1805. Then he removed to and imporved lands in another part of the then vast county of Wilkes, and that part was by later legislation cut off into the county of Taliaferro (pronounced Toliver). The name of this grandfather was Alexander Stephens. Both he and Andrew B. Stephens, the father of the subject of this sketvh, died and are no buried at this old homested place. Mr. A. H. Stephens still owns it, and it embraces about one thousand acres, worth perhaps now five thousand dollars in all. The father was an undistinguished farmer of good sense, moderate means, industry, and honesty. He died 7th May, 1826, and the devotion of his son to his memory is his best monument. The mother, Margaret Grier, was a distant relative of Justice grier of the United States Supreme Court, and sister of a humbler man, who, as calculator of the Grier Southern Almanac, for years famed for its wonderfully accurate predications of weather for the year to come, had a far higher local reputation than ever did the judge.

Of one of Mr. A.H Stephens's cousins, son of the old almanac maker, the following story is told, showing that quickness and readiness of speech was not confined to a single member of this then obscure family:

One day the corn meal of the Grier household ran short, and the son put the bridle on the old mare, a blanket on her back to keep the horse-hairs out of the meal, and , with no saddle, started for mill. A stranger overtook him on the way, and a little conversation made them aquainted. The following dialogue then took place:

STRANGER. "Then you are a son of Mr. Grier, the great almanac calculator?"

YOUNG GRIER. (modestly). "Yes, Sir."

STRANGER. "And do you ever attempt to

make calculators of the weather as your father does?"

YOUNG GRIER. "Sometimes I do, Sir."

STRANGER. "Really! And many I ask how do your calculations and your father's agree?"

YOUNG GRIER. "We are never more than two days different, I think."

STRANGER. "That is astonishing. And can you account for such remarkable agreement?" YOUNG GRIER. "Perhaps so. You see, father always knows the day before it will rain."

STRANGER. "Precisely -- I see."

YOUNG GRIER. "And I always know the day after it has rained."

The stranger cast an inquiring look at the calm face of the youth on the meal bag, and then remembered the importance of hastening on his way.

That was a day when young men of means were only ashamed of cowardice and dishonor; and doubtless the Vice-President and Congressman to be has, like henry Clar, "the mill-boy of the Slashes," "spoken his piece" from the back of a plow horse slow jogging toward a mill.

The mther of Mr. Stephens died when he was an infant, and this he justly counts the great loss of his life, not only because the accounts of her show how true and noble a mother she would have proved, but because some lack of skill (not willingness nor of kindness) and total lack of the instinct of maternity in those who reared him left him a sickly child, a weak, undeveloped man, save in brain -- if, indeed, he did not all run to brain -- and an invalid who scarcely knows what health is, save as a lull and pause in pain, even until now.

In early manhood, as shown by the one poor and faded daguerreotype existing, and before conscious power had learned to dwell in his eyes, and before men had learned to forget the appearance in the man, this lank and sallow unloveliness must have been far more trying to the sensitive youth and far more detrimental to the struggling student than those who first saw him in his prime can well understand.

Perhaps one anecdote, selected from the many in the very interesting biography published by J.R Jones, Esq., president of the National Publishing Company, will do more to show this than would any picture or description of his then life.

At the time of his beginning the practice of law in Crawfordsville -- his present home -- there was a shoe factory in that pleasant village, and one day as Mr. Stephens was walking past it very fast, as was his wont, three negroes were at the door drinking water or coffee. One of them, suspending his cup at his lips, said, loud enough to be heard by the young man, "Who is that little fel

3

[Alexander Hamilton Stephens. 389]

low that walks by here so fast of mornings?" A second replied, "Why, man, that's a lawyer." The third thought he saw the point of a capital joke, and exclaimed, "A lawyer! -- a lawyer, you say? Ha! ha! ha! that's too good!"

To one like the writer of this, who knows the capacity of negro lungs as shown in a laugh at a "corn shucking," the effect of this on the nerves of the youth can be surmised in other lights than in Mr. Stephens's after matchless telling of it. He admits that it then alarmed him as a hint of how the public might recieve him. But he was not vindictive, and in after-practice defended more negroes, without fee in many cases, and saved the lives of more, than any attorney in Georgia. It was not six months before he saved this same laughing and incredulous negro from a severe punishment for a petty crime.

A kind uncle, Aaron W. Grier, who bore the militia title of general, which then often belonged to actual Indian fighting, took the orphan home, and faithfully performed the duties of a guardian. The interest of Stephens's little patrimony, at eight per cent., paid for the cheap country tuition and clothing. He was as good a plowboy as so small a one could be, and did regular farmwork in summer. His professed piety and real morality drew the attention of a Mr. Charles C. Mills, his Sabbath-school teacher, and he undertook to loan the young Master Stephens the mpney for a better education. This put him at the higher school of Rev. Alexander Hamilton Webster, a Presbyterian, whose church he joined, and of that church he still professes to be a member. This will seem a little queer to those Nothern readers who remember the somewhat murderous intent of his challenges to Governor Herschel V. Johnson and Sentaor Benjamin H. Hill, themselves chruch members, who declined to shoot with him. Mr. Webster, whose second name, hamilton, young Alexander Stephens aftwerward took from love and gratitude, intended his young protege for the minstry, and a board, said to have consisted in part of ladies, but organzied as the Geor-

gia Education Society, agreed to furnish the means for a college. He accepted, with a proviso of liberty to return the money and act entirely upon a maturer judgement. Mr. Webster soon died, but other friends kept him at school; and in Augusta, 1828, he entered Franklin College, or the Georgia Univeristy, classical and general department, as a Freshman.

His nephew, John A. Stephens, Esq., once showed to the present writer a letter describing an incident of this journey to Athens to college, which I will attempt, no doubt imperfectlt, to give from memory. He was poor, and walked the forty or fifty miles, carrying his spare clothes upon a stick over his shoulder. A family owned a fine country-house and plantation in Greene County, just on one afternoon of his hot and dusty journey to ask a cup of cold water. This was freely given, and the tired youth was asked to spend the night, and was not treated as a mere tramp, but as a young guest. The plantation wagon gave him a lift on his way the next day, after good food, enjoyed rest, and, best of all to his hunger of heart and sensitiveness of poverty, a hospitality as genial as if he had come in the highest Georgia gentlemanly state of that period -- upon a fine horse.

Years after, when he was a greta lawyer and a member of the Congress of the United States, a widow -- Mrs. Parkes, I think -- sought him as her attorney to save her imperiled estate for herself and for her three

4

[390 HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE.]

young girls. He took the case, and he won it, as was then his habit in all of his legal battles for the right, and the widw offered the large fee which she had promised if he could win her the wherewith to pay. Not till then did he introduce himself to her as the poor lad who had asked only a "cup of cold water" on that burning Augusta day, and which he now repaid. His graititude he did not attempt to cancel by the gold pushed aside, but kept the old memory as precious as before.

During his second year at college the dawn of young ambition lured him more strongly than did any pulpit honors of that day, and his guardian gave up to him him patrimony ($444), upon which he lived for two years more, and graduated with the highest honors of that alma mater of such as Toombs, Lumpkin, Cobb, and Hill. He borrowed from A.G Stephens, his elder brother, the means to pay his debts, and went to teaching school.

On the 26th of May, 1834, he began the study of law, and made the entry of date in a pocket book or case which he still has in use. So unknown and obscure was he that the dealer asked a by-stander if he should trust him for the amount if a credit was asked for. It was not asked for, as he made no debts that he could possibly avoid. A desk in the sheriff's office (which sot him only a little writing for that county officer), Starkie on Evidence, Maddox's Chancery, Comyn's Digest, Chitty's Pleadings, and a few such elementary books, bad health, and no influential friends -- these were his means of success; and in 1843 he vacated his place in the sheriff's office for a seat in the American Congress.

When Mr. Stephens was admitted to the bar he was only twenty-two years old. He had an offer of partnership, at $1500 a year guaranteed; but the passion for home and boyhood scenes anchored him in the small but delightfully healthy town of Crawfordsville. He lived on six dollars a month, made his own fires, blacked his own boots, and made $400 in the first year.

He tells of himself, with great glee and enjoyment, a story of the beginning of his profession, on the circuit to the county sittings of the Superior Court. The next place of session was Washington, WIlkes County, the place of his better school-boy days. There was no public conveyance between the two villages. The young "squire" had no horse, and would not try to borrow one in Crawfordsville. He walked ten miles to his uncle's -- half of the distance to Washington village, and a little out of the way -- carrying his saddle-bags, containg a change of clothes, upon his shoulders. It was the July weather of the South, which means to be hot and succeeds; and he walked aat night, resting on way-side stumps, and fully aware that

his prospects were as dim as the starshine upon him. The uncle loaned the horse indispensable to even the humblest entry as a lawyer; and now the saddle-wallets, containing thin white cotton pantaloons, which were both cheap and looked like the linen of Southern summer wear, and clean shirt, were carried in the proper way. That his first appearance at the town inn as a member of the bar on his circuit might be as imposing as possible, he dismounted in a pine thicket a short distance from the first houses and put on his clean white garments. How much impressed the court and people were by this he does not say, but he does say that when he left the town he took off the still fresh garments and put on the others for his dusty ride and weary tramp home. Lord Lytton in his Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes, records of that successful orator a similar regard for appearances -- with more means.

These things, now the inspiration of wit in that polished circle at Liberty Hall -- so called by its owner because all respectable guests are made free to its bachelor comforts -- and of which many have heard the recital in his own happy way in the much-frequented reception-room in Washington city of late, were then no jest, but sad facts, that might prove cruel should helath fail or public opinion frown, and that would have been fatal had not warm hearts, like Robert Toombs, at times given him time for rest of mind and body.

Crawfordsville in 1866, just out of the utter business prostration of war, could nt probably have been better advertisement of "Wanted, carpenters and white paint," than if no repairs had been made from its civic birth in 1826. Its repulsive and gullied square; its broken-windowed court-house-- memorial of the Northern troops quartered inside, who broke them; its school-house gaping at space from glassless holes, and resting on far less than its original stone legs; its general look of out-of-pocketiveness, were no doubt all existing. But now that iron arterty of Georgia trade, the Georgia Railroad, has fed it and been fed from it, and he who this summer shall pause half-way in his ride down the ridge from Atlanta to Augusta, and rest under its green spreading oaks and China-trees, and eat of the best water-melons in the world, grown in sandy nests of the red clay, and who shall quench his thirst with that ice-cold water, or put his legs under hospitable tables laden with such fried chicken, ham and eggs, fresh figs, and grapes, as city wiaters don't handle, will vote Crawfordsville a nice town, and its neat white homes just the places in which to pass a sultry day. In that wonderful Middle Georgia it is never so hat as in New York, and never so cold; and even when the clay does stick in winter, never so nasty!

5

Just out of the town lies Stephen's home. There is so great and luxuriant