Pages That Mention Tillamook Rock

Vol 631 Tramway Winch LH Reports 1884 and 1885

21

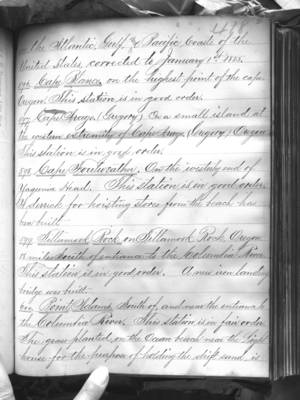

on the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific Coasts of the United States, corrected to January 1st 1885.

596 Cape Blanco on the highest point of the cape, Oregon. This station is in good order. 597. Cape Arago. (Gregory) On a small island at the western extremity of Cape Arago. (Gregory) Oregon This Station is in good order. 598. Cape Foulweather. On the westerly end of Yaquina Head. This station is in good order. A derrick for hoisting stores from the beach has been built. 599. Tillamook Rock on Tillamook Rock, Oregon. 18 miles South of entrance to the Columbia River. This station is in good order. A new iron landing bridge was built. 600. Point Adams. South of, and near the entrance to the Columbia River. This station is in fair order. The grass planted on the ocean beach near the Lighthouse for the purpose of holding the drift sand, is

Vol 601Topographical survey and lens description 1883

5

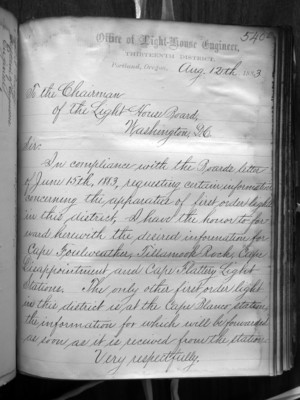

Office of Light-House Engineer, THIRTEENTH DISTRICT Portland, Oregon, August 12th, 1883

To the Chairman Of the Light-House Board, Washington, D.C.

Sir: In compliance with the Board’s letter of June 15th, 1883, requesting certain information concerning the apparatus of first order lights in this district, I have the honor to forward herewith the desired information for Cape Foulweather, Tillamook Rock, Cape Disappointment and Cape Flattery Light Stations. The only other first order light in this district is at the Cape Blanco station, the information for which will be forwarded as soon as it is received from the stations.

Very respectfully,

8

Tillamook Rock Light Station, Oreg. 1. Lens made by Henry Lefrante, Paris. First order, catadioptric Fresnal lens. Revolving, once in two minutes, with white flash every five seconds. 24 panels in lens apparatus. 18 prisms above dioptric drums. 8 “ below “ “ .

2. Funk’s 1st order hydraulic float lamps. Height from base to top of burner, 34.31 inches. 3. Distance “between centers of bolts on which the lamp directly rests”, 15.82 inches. 6. Height from focal plane of lens to lower edge of cylinder at top, 62.52 inches. Inside diameter of this cylinder 6.29 inches.

Coast Guard District narrative histories 1945

21

In the quite rapid succession, Umpqua River, Willapa Bay, Smith Island, Ediz Hook, Cape Arago, Cape Blanco, Point No Point, Point Wilson, and Yaquina Bay Lighthouses were built. In 1879, construction began on the Tillamook Rock Beacon.

Tillamook Rock Lighthouse was one of the most famous as well as one of the most exposed stations in the Lighthouse Service, set on a great precipitous rock lying a mile offshore from Tillamook Head on the Oregon Coast. A dark cloud of ill omen shadowed the station as, in the landing of the construction party, the superintendent was swept by a great wave into the sea and drowned. Almost insurmountable obstacles faced the engineers, for the entire top of the rock mass had to be blasted level to provide space for the lighthouse and its accompanying structures. Heavy seas continually washed over the Rock carrying away half finished foundations, equipment and endangering the lives of the entire work party. Although the light stood 133 feet above the water, on many occasions tremendous waves swept completely over the station carrying large fragments of rock which caused considerable damage to the station. On one such occasion, a rock weighting 135 pounds was hurled through the roof of the building and into the quarters below, causing extensive damage. Another time, the sea tossed a boulder through the lantern, extinguished the light and flooded the dwelling below.

West Point, built in 1881, Alki Point and Brown Point, built in 1887 and Destruction Island, built in 1891, were the next light stations to be erected. Here again, at Destruction Island, treacherous seas made landings difficult except in calm weather, so the "basket" and boom were again called upon for safe landings on the station. 14 other lighthouses were established in the Seattle District, the last being the Lim Kiln structure in 1914. Strangely enough, the Lime Kiln Lighthouse was the last light station in the District operating an oil lantern. An attempt was made to electrify the light by extending commercial power to the Station but the Power Company was unable to furnish sufficient current; in the same regard, poles had to be set in a solid rock and the cost and labor for this were almost prohibitive. A request was made for Headquarters' approval to install a power plant at the unit but this was not commensurate with Headquarters' policy so the light remained an incandescent oil vapor type. This type, familiarly known as i.o.v., gave good service although its range could not match that of the newer electric light. The old i.o.v. light came in two sizes and was approximately equivalent

-2-

22

to the 350 watt and 750 watt electric lamps of today; this limitation permitted slight variation in the range of the lighted beacons. The lenses increased and magnified the light as they revolved to produce a flashing effect.

Reminicenses of the Lighthouse men who tended these lights during the years when the Northwest was, for the most part, a mountainous wilderness, make interesting listening. Even after the invention of railroads, telephones and the automobile, trips to coastal Light Stations involved travel by boat, stage and horseback. Stage drivers informed passengers before the journey began, that there was no guarantee that the stage could complete the trip, in which event, the traveller made the remainder of his journey on foot. Seasonal rains, washouts, and the miserable conditions of the "roads" (deer trails, or Indian paths) made such stipulations a necessity. Today's brief trip from Bandon to Cape Blanco, Oregon, can be made either way in a fraction of an hour; earlier travellers spent three days; The uncertainty of transportation was illustrated in the following anecdote: An engineer of the Lighthouse Service was called to Destruction Island to repair the boilers. A buoy tender took the engineer to the Island and he requested that the tender return on Friday to pick him up. Friday came - and went; another Friday - no tender; a third Friday - and in the distance the curl of a tender's smoke was seen on the horizon (in those days the smoke trails of the various type ships identified them to the men whose idle hours were spent watching the horizon for the vessels that occasionally appeared there.) When the Master of the tender was admonished for his tardiness, he replied, "You said to come on Friday; isn't this Friday?". Time was of little import.

Life on the Light Stations until the middle thirties was a world of its own. Because of their locations there were no telephone facilities, and commercial electric power did not reach to the outposts. There were generally two keepers and their families assigned to each station and the competition for the most tidy and efficient station among the keepers was keen. A few of the isolated stations at Tillamook Rock, Destruction Island, Cape Flattery, etc. had four or five keepers, one on continuous liberty rotation. With the installation of radiobeacons at many of the stations, it became necessary to bring in commercial electric power or generate power at the station. With electricity available, the i.c.v. light was superceded, the fog signals mechanized, and the comforts of the keeper's dwellings increased. Telephone service or radio-telephone service soon followed as