Description

Traïson

"Quant aucuns a esté naffré ou assailli ou malmené, ou damagé, d’aucune grant choze, il peut bien venir devant le seignor et clamer soi de celui cui il le met sus, et dire que il li a ce fait fausement et desloiaument, en traïzon, sans defiance et nuitancré, se ce fu de nuit. "

"It could well happen that when someone is wounded, assaulted, mistreated or harmed in any serious manner, he can come before the lord and bring a claim against the man he accuses, saying that he has done this to him falsely and unlawfully in treason, without defiance and at night (if it were at night). "

Traïson, one of the most serious criminal offenses in the Latin East, is the topic of much discussion in Outremer legal texts. As the above quote from Philip of Novara makes clear, traïson did not necessarily correspond to our modern “treason,” that is, a crime against the state. Indeed, early-thirteenth century Anglo-Norman authors tended to use traïson less as a synonym for lèse-majesté (a crime against the king) than as a blanket term for attempts to cause harm to another that stemmed from secret hatred, involved shameful behavior, and revealed the immoral character of the traitor. The etymology of the word may be instructive, as traïson derives from the Old French verb traïr, meaning “to deliver up,” or “to betray.” This, in turn, derives from trādĕre, a Latin verb with powerful cultural connotations – being, notably, the verb used in the Vulgate to describe Judas’ betrayal of Christ. Into the late thirteenth century, Anglo-Norman legal texts and literary depictions of trials only defined a crime as traïson if it involved an underhanded act that breached a relationship of faith, love, and trust. The formal conflation of traïson with lèse-majesté in English law only occurred in 1352, decades after the fall of the Latin East.

The Anglo-Norman usage of traïson provides a useful guide to interpreting the word in Outremer contexts. In addition to the above passage from Philip of Novara, concerning duplicitous acts of violence, legal texts use the word “traïson” to refer to cases where a disloyal vassal has perjuriously claimed land that belongs to his lord or where a daughter has committed a grave offense against her parents. Those accused of traïson could either deny and rebut the charge or else engage in bataille to prove their innocence. The choice would be left to the accused unless the accuser was able to establish that the traïson was aparant, in which case denials and rebuttals would not suffice. In cases of personal assault, however, the accused’s lord could forbid bataille. The penalty for traïson was serious: a man convicted of traïson against his lord would lose his fief and the fidelity of his lord, and he would have to go into exile from the kingdom for life, on pain of death. It was, moreover, one of a very small number of crimes for which an heir could be dispossessed of their hereditary fief.

Alternative Forms: traisun; traisoun; trahisun; treason; treason; treason; treisoun; tresun; treson; tresone; tresoun

Related Terms: aparant; bataille; lèse-majesté

Related Subjects

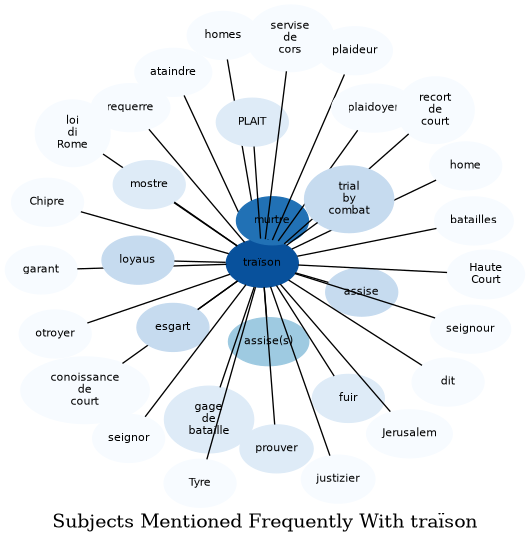

The graph displays the other subjects mentioned on the same pages as the subject "traïson". If the same subject occurs on a page with "traïson" more than once, it appears closer to "traïson" on the graph, and is colored in a darker shade. The closer a subject is to the center, the more "related" the subjects are.