Pages

31

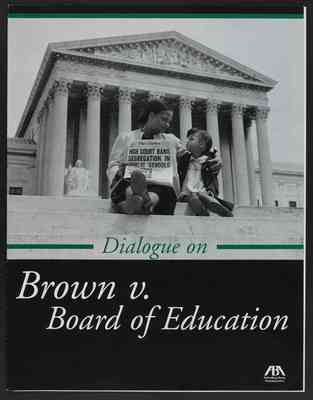

[image:] A black woman and child seated on the steps of a pillared government building. The woman holds a newspaper showing the headline "HIGH COURT BANS SEGREGATION IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS"

Dialogue on

Brown v. Board of Education

32

The Story of Brown v. Board of Education

May 17, 2004, is the fiftieth anniversary of the United States Supreme Court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The decision brought an end to the legal doctrine of "separate but equal," enshrined by the same court nearly sixty years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson. In Plessy, the Supreme Court held that segregation was acceptable if the separate facilities provided for blacks were equal to those provided for whites. The sole dissent came from Justice Harlan. Arguing that "our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens," Justice Harlan accurately predicted further "aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens."

[image:] Photograph of "Colored Waiting Room" sign with the following attribution: ©Bettmann/CORBIS; reprinted with permission.

Justice Harlan's warning was fully realized in the regime of "Jim Crow" laws that, with the Supreme Court's sanction, enforced segregation of blacks and other people of color from many of the facilities enjoyed by white citizens across much of the United States. Public schools, transportation facilities, residential neighborhoods, public and private theaters, restaurants, and even public lavatories and drinking fountains were designated for the exclusive use of "whites," while separate -- and supposedly equal -- facilities were set aside for "coloreds." Any hope of changing these laws through democratic processes was stripped away as states erected legal barriers to the exercise of the vote by black citizens. And in courthouses across the land, blacks were systematically excluded from service on juries.

Segregation was the law, but almost immediately it met with resistance. Less than fifteen years after Plessy, a group of individuals committed to fighting against the brutalities of Jim Crow America had formed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (the NAACP). And in 1926, Mordecai W. Johnson arrived as the first black president at all-black Howard University and put the institution on a crash course for academic excellence. In 1929, he hired Charles Hamilton Houston as dean of the Howard University Law School. The result of Houston's arrival and the changes he initiated was a law school curriculum taught by and capable of producing some of the greatest legal talents America has seen. Working individually and through the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund, these lawyers would change the course of American law and society.

This group of black attorneys included Houston himself, Robert L. Carter, William T. Coleman, William Henry Hastie, George Hayes, Oliver Hill, Constance Baker Motley, James M. Nabrit, Jr., Spottswood W. Robinson III, and -- perhaps most famous of all -- Thurgood Marshall. They were joined by others committed to the fight against segregation, including Jack Greenberg of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. In the decades leading up to Brown, these lawyers progressively chipped away at the legal structure fortifying segregation. All-white jury pools, covenants that restricted ownership of property in certain neighbors by race, laws disenfranchising black voters, and segregated graduate and professional schools were all challenged, often successfully. Attention then turned to the politically charged arena of public school segregation.

The legal strategy focused first on insisting that states take the Plessy standard seriously. "White" and "colored" schools were certainly separate, but in most cases they were far from equal. District by district, legal challenges were brought insisting that black schools be brought up to par with their "whites only" equivalents. This strategy, however, required fighting district by district and did not directly challenge the doctrine of "separate but equal." In 1950, the NAACP resolved that nothing other than education of all children on a nonsegregated basis would be an acceptable outcome. Work began on laying the final groundwork for Brown v. Board of Education.

The case known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas actually included appeals from decisions in four separate states: Kansas, Delaware, South Carolina, and Virginia. Each case represented individual acts of courage by families willing to face local resistance -- evan hostility -- to bring an end to segregation.

[image:] Photograph of black and white children standing together in a classroom with hands over their hearts looking at a flag raised by a young black boy. Includes the following attribution: © Bettmann/CORBIS; reprinted with permission.

Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education

1

33

School conditions in these four test cases varied, from stark differences in South Carolina between the "colored" and "white" schools to a closer parity in the Topeka, Kansas, schools. In all four states, however, the schools were segregated by law, and the NAACP's position was that equality could not be achieved until segregation was brought to an end.

Although the four decisions went against the NAACP in the trial courts, its position was strengthened by some of the decisions. In South Carolina, Judge Julius Waties Waring dissented from the opinion of his two colleagues who also heard the case, declaring that "segregation is per se inequality." And in Kansas, the three-judge panel attached to its opinion a finding of fact that segregation has a detrimental effect on colored children, especially when it is enforced by law.

The four cases were argued on appeal to the United States Supreme Court in 1952, with the issue being whether segregation depriced students of equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court requested reargument of the case in 1953. Before the reargument could occur, Chief Justice Vinson died and was replaced by Chief Justice Earl Warren. Under his guidance, a unanimous Court on May 17, 1954, issued its decision declaring that segregation of the public schools was unconstitutional. A landmark in the struggle for equality and under the law for all Americans had been achieved.

Starting the Dialogue

At the heart of Brown v. Board of Education was the desire to ensure equal protection of the laws for all Americans. The following questions ask students to reflect on what has been required -- and what has been achieved -- in pursuit of this goal in our nation's schools.

Dialogue leaders should feel free to develop their own lines of inquiry for exploring the significance of Brown v. Board of Education. Page 3-6 offer ideas for such topics as

• Issues of equality and racial diversity in America • The role of education in effecting social change • The legacy of segregation in the United States • The role of law in maintaining or changing the status quo

1. You are a classmate of Linda Brown at a segregated school in Topeka, Kansas, in 1951. She and her family have decided to challenge the idea that schools should be separated by race. Gaining admission to the "whites only" school may very well mean that members of your community will harass you and your family and that you will encounter hostility from your classmates and teachers at your new school.

Do you join Linda Brown?

2. The year is 1960. You are one of ten black students who have been admitted into a formerly "whites only" high school. In class, you struggle to get the teacher's attention to answer a question. At lunch, it is clear that you are not welcome to join most of the other students at their tables. When entering school, you often receive a glare or hear a muttered comment from parents dropping off their children.

How do you cope with life at your new school?

3. Abraham Lincoln High School is located in a community with high unemployment and low family incomes. Robert E. Lee High School is located in a prosperous community in the same state. Both Abraham Lincoln High and Robert E. Lee High receive the same amount of money per pupil from the state government. Robert E. Lee High, however, is able to collect substantially m ore local tax money from its residents and thus has significantly more money to spend on each pupil. It can attract the best teachers by offering high salaries, has a state-of-the-art computer center, and offers a wide range of courses in music and art. Abraham Lincoln High has to pay its teachers below the state average and loses many teachers each year when they leave for better paying jobs. It cannot afford even one computer per classroom. Because of budget constraints, courses in music and the arts have been eliminated. The school's athletic program is at risk of being cut.

Has the state met its obligation to provide an equal education to students at Abraham Lincoln High and Robert E. Lee High?

4. Imaging that you are a student at Robert E. Lee High School. You are told that, as a result of a new state law intended to equalize opportunity among the state's school districts, part of your school's funds must be shared with Abraham Lincoln High School. Budget cuts will mean that the school may lose its computer center and that the number of opportunities for participation in athletic, musical, and artistic events will be sharply reduced.

How do you respond?

5. You are a high school senior trying to decide where to attend college.

How important to you would it be to attend a racially diverse college? Should college be able to consider the race of applicants in trying to create a diverse student body? What should a racially diverse American college campus look like?

6. Think about the other students at your school, your circle of friends, and the people who live in your neighborhood.

To what extent do you think Brown v. Board of Education's dream of an integrated America has been made real?

ABA Division for Public Education

2

34

Exploring the Issues

The story of Brown v. Board of Education and its legacy raises a host of issues concerning American law and society. The following features offer opportunities to explore some of these issues with students. Each feature includes at least one "conversation starter" -- a brief excerpt from an essay or legal opinion, for example, or a political cartoon or photograph--that can easily be read in a few minutes. The conversation starters are followed by focus questions you can use to begin your dialogue with the students. Feel free to pick and choose among these topics -- or design your own -- according to your interests and the time you have available with the students.

What is Equality Under the Law?

I. Declaration of Independence, 1776

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.

II. Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the question before the Supreme Court was whether a Louisiana law providing for separate railway cars for whites and blacks violated the Constitution.

The object of the [Fourteenth] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality . . . If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane. -- Justice Henry Billings Brown, majority opinion

Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. -- Justice John Marshall Harlan, dissenting

III. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. -- Chief Justice Earl Warren, for a unanimous Court

IV. Grutter v. Bollinger, No. 02-241 (2003)

The issue before the Court in Grutter v. Bollinger was whether the University of Michigan Law School could use race as a consideration in admitting students.

Government may treat people differently because of their race only for the most compelling reasons . . . Today we endorse [the] view that student body diversity is a compelling state interest that can justify the use of race in university admissions. -- Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, majority opinion

[R]acial classifications are per se harmful and . . . almost no amount of benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify such classifications. -- Justice Clarence Thomas, dissenting

Focus Questions

1. What does "created equal" mean to you? People are obviously very different, so what, exactly, do we mean by "equality"? Equality of opportunity? Equal treatment under law? Equal treatment for similarly situated individuals?

2. The doctrine of "separate but equal" upheld in Plessy put African Americans at a severe disadvantage. The practice upheld in Grutter gave African Americans and members of certain other minorities an advantage in the law school's admission policy.

The dissents in both cases essentially argued that the Constitution is color-blind. What does that mean? Is the Constitution color-blind? Should it be?

3. How should we deal with the possible harm to some individuals caused by preference established to advance the interests of members of historically disadvantaged groups? Does the "benign" intention of the preference make a difference?

Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education

3

35

Should Schools Serve as Laboratories for Social Change?

I. Brown v. Board of Education (II), 349 U.S. (1955)

The unanimous Brown decision in 1954 didn't specify how (or how quickly) desegregation was to be achieved in the thousands of segregated school systems. The case was reargued on the question of relief, and on May 31, 1955 (almost exactly one year after the first decision), the Court issued an opinion, commonly referred to as Brown II.

The NAACP urged desegregation to proceed immediately, or at least within firm deadlines. The states claimed both were impracticable. The Court, fearful of hostility or even violence if the NAACP views were adopted, embraced a view close to that of the states. . . . [e]ssentially return[ing] the problem to the courts where the cases began for appropriate desegregative relief -- with . . . "all deliberate speed." . . . By 1964, a decade after the first decision, less than 2 percent of formerly segregated school districts had experienced any desegregation. -- Dennis J. Hutchinson, "Brown v. Board of Education," in the Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States

[image:] Cartoon showing a man (labeled "SOUTH") using a horse (labeled "GRADUALISM") to plow a field (labeled "STEADY PROGRESS IN RACE RELATIONS"). Another man comes from behind him leading a horse while saying, "YOU'RE NOT GOING FAST ENOUGH -- TRY THIS ONE." The Cartoon is captioned: "No job for a race horse." Attributed to John Kennedy, May 22, 1954, Arkansas Democrat. Reprinted with permission of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette

II. Little Rock Central High School, 1957

Little Rock Central High School was supposed to be desegregated by the beginning of the 1957 school year. On September 2, the night before the first day of school, Governor Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to monitor the school. The next day, the Guardsmen prevented nine black children from entering the school. On September 20, a Federal District Court issued an injunction that prevented Governor Faubus from using the National Guard to deny the students admittance to Central High. When the nine students returned to the school, however, police removed them for their own protection after a mob of 1,000 people around the school grew unruly. President Eisenhower intervened, sending 1,000 paratroops and 10,000 National Guardsmen to Little Rock. The Little Rock Central High School was finally desegregated on September 25, 1957.

Looking back on this year will probably be with regret that integration could have been accomplished peacefully, without incident, without publicity. -- Georgia Dortch and Jane Emery, co-editors of The Tiger (Little Rock Central High student newspaper), October 3, 1957

Focus Questions

1. Reaction to the first Brown decision was fierce in the Southern states, with newspaper editorials predicting violence and political leaders promising defiance. How do you think the Court's ruling for desegregation with "all deliberate speed" should have been interpreted? Do you think it gave too much deference to white resistance in the South? What do you think the result would have been had the Court demanded immediate desegregation? What would you have done as a justice in the same situation?

2. What can the Supreme Court do to enforce its decisions? What is the role of the other branches in enforcing Court decisions? What can the Court do without the full support of the other branches?

3. Why do you think schools were the focus of the litigation that led to the decision in Brown v. Board? Is it more important for schools to be diverse and desegregated than the rest of society?

4. What do you think are the possible problems and risks involved in using schools as the site of social reform?

5. Statistics show that schools that once were segregated by law have often "resegregated," not as a result of law but of housing patterns and other circumstances. Is the "voluntary" resegregation of our nation's schools harmful? In terms of effect on students, is there a difference between legally m andated segregation and segregation due to other factors? What should national, state, or local governments do about this issue?

ABA Division for Public Education

4