Pages

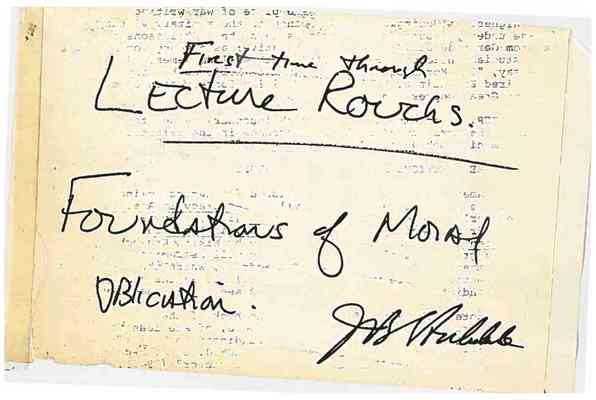

First time through LECTURE ROUGHS.

Foundations of Moral Obligation.

J. B. Stockdale

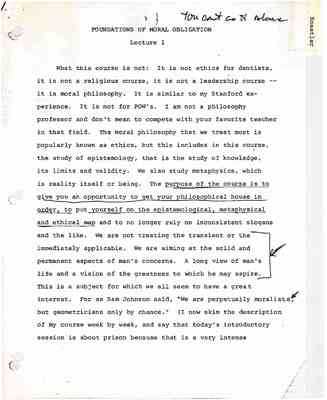

You can't Go it Alone [handwritten]

FOUNDATIONS OF MORAL OBLIGATION

Lecture 1

What this course is not: It is not ethics for dentists, it is not a religious course, it is not a leadership course -- it is moral philosophy. It is similar to my Stanford experience. It is not for POW's. I am not a philosphy professor and don't mean to compete with your favorite teacher in that field. The moral philosophy that we treat most is popularly known as ethics, but this includes in this course, the study of epistemology, that is the study of knowledge, its limits and validity. We also study metaphysics, which is reality itself or being. The purpose of the course is to give you an opportunity to get your philosophical house in order, to put yourself on the epistemological, metaphysical and ethical map and to no longer rely on inconsistent slogans and the like. [Marginal bracket with arrow starts] We are not treating the transient or the immediately applicable. We are aiming at the solid and permanent aspects of man's concerns. A long view of man's life and a vision of the greatness to which he may aspire. [Marginal bracket with arrow ends] This is a subject for which we all seem to have a great interest. For as Sam Johnson said, "We are perpetually moralists [arrow], but geometricians only by chance." (I now skim the description of my course week by week, and say that today's introductory session is about prison because that is very intense

environment in which issues surface readily and frequently.) And the message is unity over self. That none of us have the luxury of maintaining aloofness in an activist, competitive profession. Whether it be aboard ship or in an airplane or in an infantry company, we must be each other's servants.

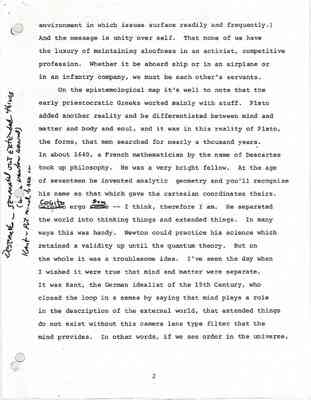

On the epistemological map it's well to note that the early priestocratic Greeks worked mainly with stuff. Plato added another reality and he differentiated between mind and matter and body and soul, and it was in this reality of Plato, the forms, that men searched for nearly a thousand years. In about 1640, a French mathematician by the name of Descartes took up philosophy. He was a very bright fellow. At the age of seventeen he invented analytic geometry and you'll recognize his name as that which gave the cartesian coordinates theirs. ??Cargito?? Cogito ergo ??smine??sum -- I think, therefore I am. He separated the world into thinking and extended things. In many ways this was handy. Newton could practice his science which retained a validity up until the quantum theory. But on the whole it was a troublesome idea. I've seen the day when I wished it were true that mind and matter were separate. It was Kant, the German idealist of the 19th Century, who closed the loop in a sense by saying that mind plays a role in the description of the external world, that extended things do not exist without this camera lens type filter that the mind provides. In other words, if we see order in the universe,

might it not be just a function of our lens rather than reality itself? Of course we pay more attention to his Kant's ethical theories, in which he relies heavily on the motive of acts and on the morality of acts themselves. His opinion is the opposite of that of the academic who succeeds him in our course; John Stewart Mill, who says the motive in immaterial it's the results that count. And Mill was the prototype of the 19th Century English liberal, who became famous for the forwarding of such ideas aas the inalienable natural rights of man and of unfettered individualism. But w/i confines of Reason. The political manifestation of this 19th Century English liberalism was self-determination and internationalism. The balance of power, and the economic manifestation through the industrial revolution was laissez-faire economics. The great celebration of the gay '90's centered on this optimism. But certain novelists, particularly Dostoyevsky, had already suggested that all of this was about to collapse in a spiritual vacuum. That the stability of the church, in of the Guild guild of the village, of the home, had given way to the relative instability, and certainly more impersonal, factory, barracks (conscription was in effect in many European countries, The public schools, (and city life). The balance of power dream burst at Sarajevo in 1914 and the economic dream of laissez-faire met its Waterloo in the depression of 1929. Now I've given unusual concentration to the 19th Century for the simple reason that I want to introduce Vladimir Ilich Lenin, who made today's story, Darkness At Noon possible.

3

5

Lenin is thought by some historians to have been the man of the 20th Century. A true fanatic, a genuine idealist, and a tough practitioner of realpolitik who advocated cheating, lying on a zigzag trail toward worthy ends -- any means to his ends. Sometimes he is described as Hitler with a purpose.

You'll remember that in 1917 Russia was still in World War I in opposition to Germany, a revolution had taken place, the Mensheviks were in power and their leader was Alexander Kerenski. (Kerenski was director of the Hoover Library when I studied there in the early 1960's). Kerenski was sort of a socialist under the banner of "all power to the Soviets." Lenin arrived in an armored train from Germany and within a month had overthrown him as a leader of the Bolshevik party under the more practical slogan of bread, peace and land. He recalled Trotsky from New York, as the greatest Jew since Jesus Christ. But as you remember they later fell out over the issue of world revolution versus socialism in one country. Lenin died in 1962 24?; Stalin succeeded him in 1926. Lenin was a poor Marxist and Stalin might have been a poor Leninist. But it was Lenin who gave the modern ideology its name. He was tough, ruthless, and like many of the old ideologues, had a certain legitimacy that gave him a constituancy through which he could operate. At the recent IISS Conference one of the hardnosed Scottish anti-communists 4