Pages

page_0001

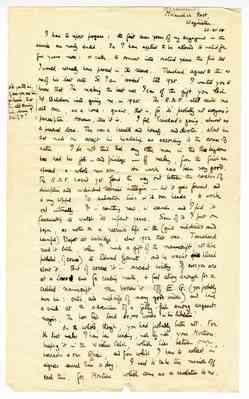

Miranshah Fort, Waziristan.

26.xii.28

I have to report progress: the first seven years of my engagement in the service are nearly ended. So I have applied to be allowed to extend for five years more: or rather, to convert into active years the five that I would normally have passed in the reserve. Trenchard agreed to this, as one of his last acts. So I am "booked" till 1935. I wanted you to know that I'm making the best use I can of the gift you led Mr Baldwin into giving me in 1925. The R.A.F. still suits me [in margin: Will you tell him if ever you see him at leisure, that I'm still thanking him, whenever I think of it?] all over, as a home: quaint, that is, for it's probably not everyone's prescription. However, there it is. I feel Trenchard's going, almost as a personal loss. There was a breadth and honesty, and devotion, about him that made one accept his headship as according to the course of nature. I do not think that any other man in the three kingdoms has had his job - and privilege - of making, from the first man upward, a whole new arm. His work has been very good. The R.A.F. hasn't yet found the way out between the rocks of discipline and individual technical intelligence - but it goes forward, and is very hopeful. Its salvation lies in its own heads, to work out internally. It is something new, in services, and I find it fascinating to watch its infant years. Some of it I put on paper, as notes on a recruit's life in the (quite misdirected and harmful) Depot at Uxbridge: about 1922 that was. Trenchard read it lately, when I made a gift of the manuscript (not to be published, of course) to Edward Garnett: and he wasn't pleased about it. But of course it is ancient history. If ever you are at a loose end for reading matter, and feel strong enough for a crabbed manuscript, then borrow it off E.G. (you probably know him: critic, and midwife of many good writers) and have a smile at the adventures of a jelly-fish among sergeant- majors. The poor fish laid 80,000 words in his tribulation!

On the whole,though, you had probably better not. For the last weeks I have been reading, inch by inch, your Montrose: keeping it in the Wireless Cabin, which lies between our barracks and our offices, and from which I have to collect "in" signals several times a day. I used to take ten minutes off each time, for Montrose, which came as a revelation to me.

page_0002

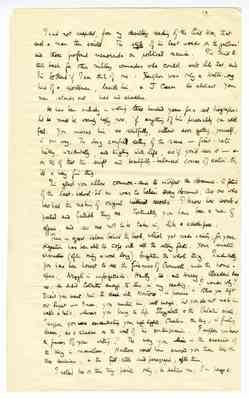

2)

I had not suspected, from my desultory reading of the Civil War, that such a man then existed. The style of his last words on the gallows! and those profound memoranda on political science. I've tried to think back for other military commanders who could write like that, and I'm bothered if I can think of one: Xenophon was only a Walter-Long kind of a sportsman, beside him, & J. Caesar too abstract. Your man stands out, head and shoulders.

He has been unlucky in waiting three hundred years for a real biographer: but he must be warmly happy, now, if anything of his personality can still feel. You unwrap him so skilfully, without ever getting, yourself, in our way. The long careful setting of the scene - first-rate history, incidentally, and tingling with life, as if you'd seen it - & on top of that the swift and beautifully-balanced course of action. Oh, it's a very fine thing.

I'm glad you allow common-sense to interpret the documents. A fetish of the last-school-but-one was to believe every document. As one who has had the making of original historical records I know how weak & partial and fallible they are. Fortunately you have been a man of affairs, and so are not to be taken in, like a scholar pure.

There is great labour behind the book, which yet reads easily, for your digestion has been able to cope with all the stony facts. Your small characters (often only a word long) brighten the whole thing. Incidentally, you have been honest to see the fineness of Cromwell, under the home- spun. Argyll is unforgettable: Huntly, too: and Hurry. Alasdair less so. He didn't Colkitto enough to live in my reading. I wonder why? Didn't you want him to clash with Montrose, in prowess? Also you left out Rupert - I mean, you mention him, well enough, but you do not make him walk & talk, whereas you bring to life Elizabeth & the Palatine circle. I suppose you were concentrating your high lights. Charles, the king, is finely drawn, as a shadow on the wall of his contemporaries. I suppose you know the fineness of your writing? The way you line in the execution of the King is marvellous. Montrose would have envied you those two or three sentences, & the full-stop and paragraph, after them.

I noticed two or three tiny points only, to distress me. On page 61

page_0003

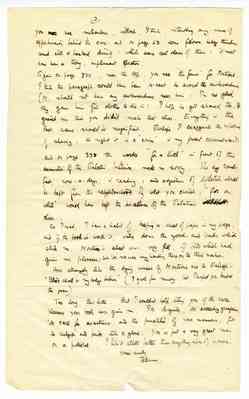

3)

you use meticulous, without, I think, intending any sense of apprehension behind the care: and on page 63 some fellows hedge themselves round with a bastard divinity: which was real clever of them: it must have been a thorny, unpleasant operation.

Again on page 330, near the top, you use "the former" for Montrose. I think the paragraph could have been re-cast, to avoid the awkwardness (M. should not have any awkwardness near him: I'm so glad they gave him fine clothes to die in: I hope he got shaved, too. It grieved me that you didn't make that clear. Everything in the last scene should be magnificent. Perhaps I exaggerate the importance of shaving: to neglect it is a "crime" in my present circumstances!) and on page 338 the words "for a little" in front of the summation of the Palatine brilliance made me sorry. The eye travels fast, now-a-days, in reading: and adjectives of deflation should be kept from the neighbourhood of what you cherish: "for a while" would have kept the excellence of the Palatines clear.

As I read, I have a habit of keeping a sheet of paper in my page, and if the book is worth it, writing down the goods and bads which strike me. Montrose's sheet was very full, of bits which had given me pleasure: but it's no use my handing these on to their maker.

How strangely like the dying verses of Montrose are to Raleigh's "Blood shall be my body's balmer" (I quote from memory, but I expect you know the poem).

Too long, this letter. But I couldn't help telling you of the rare pleasure your book has given me. Its dignity, its exceeding gracefulness, its care for exactness, and the punctilio of your manners, fit its subject and period like a glove. You've put a very great man on a pedestal. I like it streets better than anything else of yours.

Yours sincerely

TE Shaw.