Pages

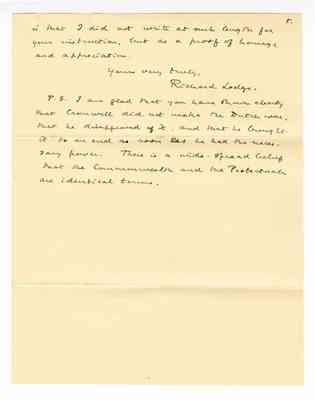

page_0001

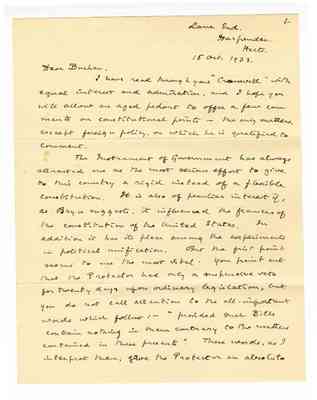

Lane End Harpenden Herts

15 Oct. 1933.

Dear Buchan.

I have read through your "Cromwell" with equal interest and admiration, and I hope you will allow an aged pedant to offer a few comments on constitutional points - the only matters, except foreign policy, on which he is qualified to comment.

The Instrument of Government has always attracted me as the most serious effort to give to this country a rigid instead of a flexible constitution. It is also of peculiar interest if, as Bryce suggests, it influenced the framers of the constitution of the United States. In addition it has its place among the experiments in political unification. But the first point seems to me the most vital. You point out that the Protector had only a suspensive veto for twenty days upon ordinary legislation, but you do not call attention to the all-important words which follow:- "provided such Bills contain nothing in them contrary to the matters contained in these presents". These words, as I interpret them, gave the Protector an absolute

page_0002

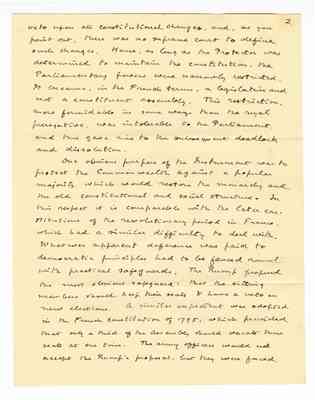

2.

veto upon all constitutional changes, and, as you point out, there was no supreme court to define such changes. Hence, as long as the Protector was determined to maintain the constitution, the Parliamentary powers were narrowly restricted. It became, in the French terms, a legislative and not a constituent assembly. This restriction, more formidable in some ways than the royal prerogatiave, was intolerable to the Parliament, and this gave rise to the subsequent deadlock and dissolution.

One obvious purpose of the Instrument was to protect the Commonwealth against a popular majority which would restore the monarchy and the old constitutional and social structure. In this respect it is comparable with the later constitutions of the revolutionary period in France which had a similar difficulty to deal with. Whatever apparent deference was paid to democratic principles had to be fenced round with practical safeguards. The Rump proposed the most obvious safeguard: that the sitting members should keep their seats & have a veto on new elections. A similar expedient was adopted in the French constitution of 1795, which provided that only a third of the Assembly should vacate their seats at one time. The army officers would not accept the Rump's proposal, but they were faced

page_0003

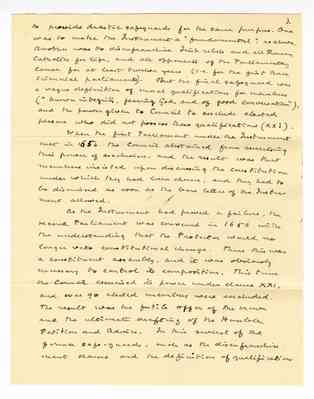

3.

to provide drastic safeguards for the same purpose. One was to make the Instrument a "fundamental", as above. Another was to disenfranchise Irish rebels and all Roman Catholics for life, and all opponents of the Parliamentary cause for at least twelve years (i.e. for the first three triennial parliaments). But the final safeguard was a vague definition of moral qualifications for members ("known integrity, fearing God, and of good conversation"), and the power given to Council to exclude elected persons who did not possess these qualifications (xxi).

When the first Parliament under the Instrument met in 1654 the Council abstained from exercising this power of exclusion, and the result was that members insisted upon discussing the constitution under which they had been chosen; and they had to be dismissed as soon as the bare letter of the Instrument allowed.

As the Instrument had proved a failure, the second Parliament was convened in 1656 with the understanding that the Protector would no longer veto constitutional change. Thus this was a constitutent assembly and it was obviously necessary to control its composition. This time the council exercised its power under clause XXI, and over 90 elected members were excluded. The result was the futile offer of the crown and the ultimate drafting of the Humble Petition and Advice. In this several of the former safe-guards, such as disenfranchisement clauses and the definition of qualifications

page_0004

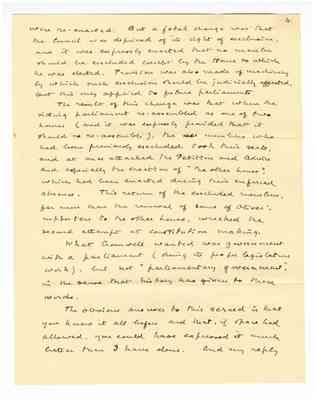

4.

were re-enacted. But a fatal change was that the Council was deprived of its right of exclusion, and it was expressly enacted that no member should be excluded except by the House to which he was elected. Provision was also made of machinery by which such exclusion should be judicially effected, but this only applied to future parliaments.

The result of this change was that when the sitting parliament re-assembled as one of two houses (and it was expressly provided that it should so re-assemble), the members who had been previously excluded took their seats, and at once attacked the Petition and Advice and especially the creation of "the other house", which had been enacted during their enforced absence. This return of the excluded members, far more than the removal of some of Oliver's supporters to the other house, wrecked the second attempt at constitution making.

What Cromwell wanted was government with a parliament (doing its proper legislative work), but not "parliamentary government", in the sense that history has given to these words.

The obvious answer to this screed is that you knew it all before and that, if space had allowed, you could have expressed it much better than I have done. And my reply

page_0005

5.

is that I did not write at such length for your instruction, but as a proof of homage and appreciation.

Yours very truly,

Richard Lodge

P.S. I am glad that you have shown clearly that Cromwell did not make the Dutch war, that he disapproved of it, and that he brought it to an end as soon as he had the necessary power. There is a wide-spread belief that the Commonwealth and the Protectorate are identical terms.