Pages

page_0001

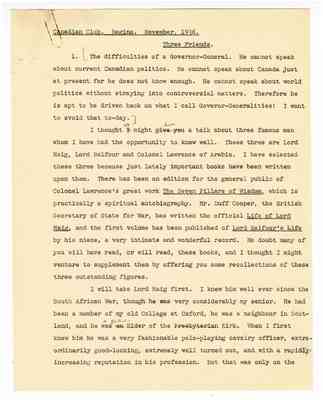

Canadian Club. Regina. November, 1936.

Three Friends.

1. The difficulties of a Governor-General. He cannot speak about current Canadian politics. He cannot speak about Canada just at present for he does not know enough. He cannot speak about world politics without straying into controversial matters. Therefore he is apt to be driven back on what I call Goveror-Generalities! I want to avoid that today.

I thought we might have a talk about three famous men whom I have had the opportunity to know well. These three are Lord Haig, Lord Balfour and Colonel Lawrence of Arabia. I have selected these three because just lately ±mportant books have been written upon them. There has been an edition for the general public of Colonel Lawrence's great work The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which is practically a spiritual autobiography. Mr. Duff Cooper, the British Secretary of State for War, has written the official Life of Lord Haig, and the first volume has been published of Lord Balfour's Life by his niece, a very intimate and wonderful record. No doubt many of you will have read, or will read, these books, and I thought I might venture to supplement them by offering you some recollections of these three outstanding figures.

I will take Lord Haig first. I knew him well ever since the South African War, though he was very considerably my senior. He had been a member of my old College at Oxford, he was a neighbour in Scotland, and he was a fellow Elder of the Kirk. When I first knew him he was a very fashionable polo-play1ng cavalry officer, extraordinarily goodlooking, extremely well turned out, and with a rapidly increasing reputation in his profession. But that was only on the

page_0002

2.

surface. The real man was the typical self-contained Scot whose inner life was concealed, except from a few intimate friends. He had all the traditional Scottish characteristics. You remember Sir Walter Scott saying, "I was born a Scotsman and a bare one; therefore I was born to fight my way in the world, with my left hand if my right hand fail me, and with my teeth if both were cut off." Haig had always this determination to make his mark in the world, for he was conscious of great talents, and he had amazing industry and patience. But there was another side to him which was also very Scottish. He had a great deal of the talents, and he had amazing industry and patience. But there was another side to him which was also very Scottish. He had a great deal of the Covenanter in him. Some time before the Great War he became deeply religious, and his religion, to the end of his life, was the mainspring of his character. Wherever his Headquarters were pitched he had his little tin church and a Scottish chaplain. He was a regular attender at the Sunday services, and I well remember when I was on his staff how, when I did not turn up at these services, he used to give me a talking to. During a battle he was a regular communicant.

He was an extremely shy man without any gift of speech. To entertain distinguished visitors at Headquarters was always a torture to him, and I remember I used to try and arrange that the conversation on such occasions should be guided towards some subject on which I knew he was able to offer a few remarks. He was very ready with his pen, and every sentence he wrote went straight to the mark, but he was simply without the power of expressing himself in the spoken word except at Staff conferences. He had none of the gift which Lord Roberts and Lord French had of talking in a friendly way to troops. (Story).

page_0003

3·

This inability to communicate readily with other people made it very difficult for him, both in dealing with his French colleagues, and, above all, in dealing with the War Cabinet at home. He had very little gift for establishing easy relations with people of another type from himself. Take Foch, for example. For Foch he had a sincere respect and the two worked admirably together in the last months of the War; but Foch's mercurial and almost melodramatic nature scared the sober Scotsman in Haig, and for long made him distrustful.

The cardinal difficulty was, of course, Mr. Lloyd George, who was the extreme opposite type to Haig in every possible way. Now Mr. Lloyd George is a really great man and in the War did incalculable service to the cause of the Allies. He has since published a big book on his War experiences - the last volume is just out and he has dealt very severely with Haig's work. Let me say frankly that I think some of the criticism is justified, though I do not greatly admire the temper in which Mr. Lloyd George writes. One of the misfortunes of the War was that there was no real opportunity for these two men coming closely together. The conduit pipe between them was Sir William Robertson, and it was too narrow a conduit pipe ever to get Mr. Lloyd George's views over to Haig, or Haig's over to Mr. Lloyd George. Mr. Lloyd George's conclusion, I gather, is that Haig was an inferior soldier, and that the War was won in spite of him. I do not believe that that can be the view of any fair-minded man who knows much about the subject. Haig was the only possible man for the extraordinarily difficult position in which the British Army found itself. A more mercurial type of man with less patience, a man

page_0004

4.

more interested in keeping up his own reputation, would have cracked halfway through. I think it fair to say that he was slow to learn; bit when he did learn he learned completely. He was a great trainer of troops - perhaps the greatest in British military history since Sir John More. He was also a master of tactics. As you know, the Great War worked a tactical revolution. The British Army was the real pioneer in new weapons and their use, and it became a lesson I remember on the third day of the Battle of to all the Allies. I remember on the third day of the Battle of Arras sitting up half the night with Lord Haig. It was just after the disaster to the cavalry at Monchy, which convinced him that cavalry could no longer be used according to the old tradition. His mind turned at once to light tanks, and I remember he said that in a year's time, when we had sufficient light tanks, we would win the War. His forecast, I need not remind you, came true fifteen months later when, on May 14th 1918, with the aid of light tanks and with the Canadian Army as a spearhead, we dealt at Amiens a final blow to Germany.

But if I had to select the greatest thing in Haig's career it would be his attack on the Hindenburg Line in October 1918. He was convinced that the War should be brought to an end in November, although everybody at home believed that it must last for another year. His view was that if the War did not end before Christmas it might mean the breakdown of civilisation altogether, and he was resolved to prevent that. So, as you know, he decided to attack the Hindenburg Line in spite of the doubts of his French colleagues and the discouragement of the War Cabinet. He had to make the decision alone. If he failed the responsibility would lie wholly on his shoulders and it might mean the destruction of a large part of the British forces

page_0005

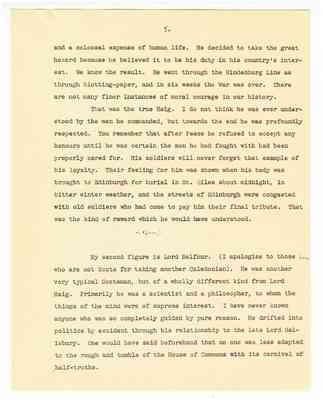

5·

and a colossal expense of human life. He decided to take the great hazard because he believed it to be his duty in his country's interest. We know the result. He went through the Hindenburg Line as through blotting-paper and in six weeks the War was over. There are not many finer instances of moral courage in our history.

That was the true Haig. I do not think he was ever understood by the men he commanded but towards the end he was profoundly respected. You remember that after Peace he refused to accept any honours until he was certain the men he had fought with had been properly cared for. His soldiers will never forget that example of his loyalty. Their feeling for him was shown when his body was brought to Edinburgh for burial in St. Giles about midnight, in bitter winter weather, and the streets of Edinburgh were congested with old soldiers who had come to pay him their final tribute. That was the kind of reward which he would have understood.

My second figure is Lord Balfour. (I apologise to those here who are not Scots for taking another Caledonian). He was another very typical Scotsman, but of a wholly different kind from Lord Haig. Primarily he was a scientist and a philosopher, to whom the things of the mind were of supreme interest. I have never known anyone who was so completely guided by pure reason. He drifted into politics by accident through his relationship to the late Lord Salisbury. One would have said beforehand that no one was less adapted to the rough and tumble of the House of Commons with its carnival of half-truths.