Pages

page_0001

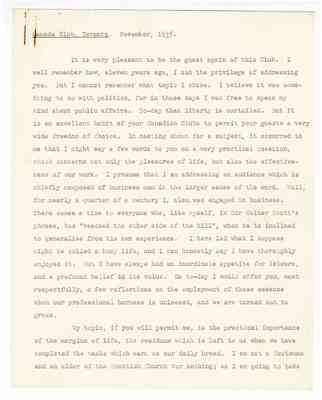

Canada Club, Toronto. November, 1935.

It is very pleasant to be the guest again of this Club. I well remember how, eleven years ago, I had the privilege of addressing you. But I cannot remember what topic I chose. I believe it was something to do with politics, for in those days I was free to speak my mind about public affairs. Today that liberty is curtailed. But it is an excellent habit of your Canadian Clubs to permit your guests a very wide freedom of' choice. In casting about for a subject, it occurred to me that I might say a few words to you on a very practical question, which concerns not only the pleasures of life, but also the effectiveness of our work. I presume that I am addressing an audience which is chiefly composed of business men in the larger sense of the word. Well for nearly a quarter of a century I, also, was engaged in business. There comes a time to everyone who, like myself, in Sir Walter Scott 's phrase, has "reached the other side of the hill", when he is inclined to generalise from his ovm. experience. I have led what I suppose might be called a busy life, and I can honestly say I have thoroughly enjoyed it. But I have always had an inordinate appetite for leisure, and a profound belief in its value. So today I would offer you, most respectfully, a few reflections on the employment of those seasons when our prpfessional harness is unloosed, and we are turned out to grass.

My topic, if you will permit me, is the practical importance of the margins of life, the residuum which is left to us when we have completed the tasks which earn us our daily bread. I am not a Scotsman and an elder of the Scottish Church for nothing; so I am going to take

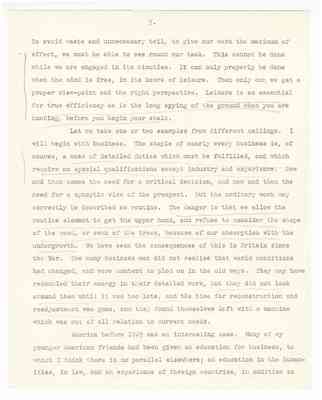

page_0002

2.

a text, and it shall be from the Book of Ecclesiasticus, "The wisdom of the learned man cometh by opportunity of leisure; and he that hath little business shall become wise." After the fashion of the old type of Scottish minister, I would add that I am especially concerned with the first clause of the verse, for I do not think the second clause is equally sound: "Wisdom cometh by opportunity of leisure."

This is an immense subject, and I want to limit myself to one practical aspect of it. There are many aspects. For example, there is the sociological and economic side. We are all agreed that one of the chief objects of education is to enrich our leisure, and that the policy of shorter hours of work carries with it the obligation to enable the worker to employ his spare time worthily. Today we are witnessing the triumph of the machine, through which the monotonous, exacting manual toil of the past is to a large extent done away with. A mechanised world means, in the long run, a very drastic reconstruction of industry, under which labour nay be rationed with fewer working hours, and the enforced leisure thus created will have to be filled up with new employments and new interests. There are some - and I strongly sympathise with them - who dream of a world where a man will have comparatively few hours of regular work, and the rest of the day he will be craftsman or farmer, producing the necessaries, and some of the luxuries, of his life. The machine may end by playing the part which slave labour played in the old Greek world, and be the basis of a richer and more civilised life for all.

Then there is the cultural side of leisure. If we are to live a full and worthy life we cannot live only for our professions. We are human beings as well as doctors, accountants, lawyers and engineers, and

page_0003

3·

we have to get satisfaction out of life as well as a living. If we are wise, we will preserve intellectual interests wider than our actual vocations, things which keep the mind alive and keep us in touch with other aspetts of the world. There is the aspect, for example, which we reach througb books and the various forms of art. There is the aspect which we reach through a love of wild nature, and you in Canada have magnificent chances for that. There is the aspect which we reach through sport. Sir Andrew Aguecheek, you remember, in Twelfth Night, complained that to acquire foreign tongues you must give up time which might have been devoted to bear-baiting. We dare not minimise the importance of what we might call the year-baiting side of life. All these varied interests keep a man young. The late Lord Bryce was the most astonishing example I have ever known of the power of engrossing hobbies to preserve youth. I remember him telling me, when he was well over eighty, with the glee of a boy, that he was getting enormous pleasure in planning out a new life of Justinian, which he proposed to write. And if you went for a walk with him, even in his last years, his interest in everything he saw and heard was like that of a child on holiday.

But I am going to limit my subject to the sternly practical. My argument is that leisure - rightly used leisure - is essential to the success of our professional work itself. This applies, I think, to every calling I know, to every learned or skilled profession, and to every branch of commerce or industry. The secret of success is to do a job efficiently with the minimum of labour. This doe s not mean the ordinary labour-saving appliances, which often complicate work, but it does mean preliminary thought and reflection. Most jobs are done with an absurd waste of labour. Let me give you an example from a subject about

page_0004

4.

which I once knew a little - military intelligence, When the Great War began, most people thought the proper way to obtain a surprise was by an immense and elaborate secretiveness in every detail, even the smallest. At first our own authorities carried this to a ridiculous length, while Germany carried it still further, with the result that there was a Herculean effort after secrecy, which meant the employment of thousands of officials and the expenditure of vast sums of money. It failed, as it was bound to fail, Then, very slowly, we learned our folly and made some attempt to find out what we really wanted. For the true art of secrecy is to be so open about ninety-nine percent of your subject that the remaining one percent is the more easily hidden, because its existence is unrealised. Before the close of the War we used to let the enemy have an enormous amount of true information about things which did not matter, and thereby concealed the better the small fraction which mattered everything.

Most of us are apt to have a feeling at the back of our heads that the more work we put into a thing, the better we shall do it. I believe that this idea originally arose from Puritan theology, which took a grave view of life, and considered that it should be divided strictly between work and devotional exercises. The spirit is perpetuated in our hymns - "Give every flying minute something to keep in store," - a very sensible piece of advice if you interpret the "something" with reasonable generosity. But the fact is that you can easily put too much work into a job; what you cannot put too much of, is intelligence. Undue emphasis upon solid plodding work and not enough upon fruitful leisure, means that a task does not get sufficient preliminary preparation, and therefore our efforts may be largely wasted.

page_0005

5.

To avoid waste and unnecessary toil, to give our work the maximum o:f effect, we must be able to see round our task. This cannot be done while we are engaged in its minutiae. It can only properly be done when the mind is free, in its hours of leisure. Then only can we get a proper view-point and the right perspective. Leisure is as essential for true efficiency as is the long spying of the ground when you are hunting, before you begin your stalk.

Let me take one or two examples from different callings. I will begin with business. The staple of nearly every business is, of course, a mass of detailed duties which must be fulfilled, and which require no special qualifications except industry and experience. Now and then comes the need for a critical decision, and now and then the need for a synoptic view of the prospect. But the ordinary work may correctly be described as routine. The danger is that we allow the routine element to get the upper hand, and refuse to consider the shape of the wood, or even of the trees, because of our absorption with the undergrowth. We have seen the consequences o:f this in Britain since the War. Too many business men did not realise that world conditions had changed, and were content to plod on in the old ways. They may have redoubled their energy in their detailed work, but they did not look around them until it was too late, and the time for reconstruction and readjustment was gone, and they found themselves left with a machine which was out of all relation to current needs.

America before 1929 was an interesting case. Many of my younger American friends had been given an education for business, to which I think there is no parallel elsewhere; an education in the humanities, in law, and an experience of foreign countries, in addition to