Pages

page_0001

Upper Canada Bar.. (Feb 21 '36) Toronto

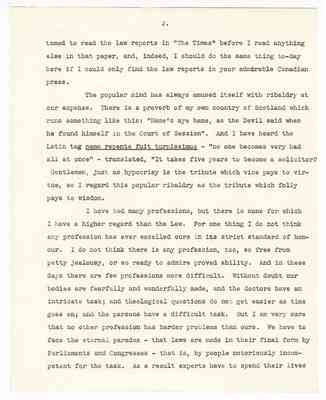

You have done me a great honour and a great kindness, for which I offer you my sincerest thanks. It delights me to be back again among lavzyers, for I feel that I am renewing my youth. In the words of the Roman poet, I, too, have lived in Arcadia; I, too, have been a lawyer. Thirty-five years ago I was called to the English Bar, after having been ploughed once in my Bar Final in company with a friend who is today one of the chief ornaments of the English Bench. I am, in a sense, a link with the past, for I was the last pupil of that great man, John Andrew Hamilton, afterwards Lord Sumner, before he took silk. I devilled occasionally for Sir Robert Finlay in the days when he was Attorney-General. On the advice of Lord Haldane I wrote a law book on that obscure topic The Taxation of Foreign Income, which was for a good many years the only treatise on the subject. So, gentlemen, you will see that at one time in my life I was really respectable.

Then I fell from grace. I left the pastoral uplands of the law for the low levels of commerce, and in my future relations with Courts of Justice I had to content myself either with the insignificant position of the lay client, or the dulness of the jury box, or the witness box, though so far I have escaped the garish and uncomfortable notoriety of the dock. But now I seem to have been forgiven my backsliding. Last summer I was made a Bencher of my old Inn, the Middle Temple; today you have deeply honoured me by making me an honorary member of the Bar of Upper Canada.

But though I ceased to practise law I did not lose my interest in it. Once a lawyer, always a lawyer. At home I have been accus-

page_0002

2.

tomed to read the law reports in "The Times" before I read anything else in that paper, and, indeed, I should do the same thing today here if I could only find the law reports in your admirable Canadian press.

The popular mind has always amused itself with ribaldry at our expense. There is a proverb of my own country of Scotland which runs something like this: "Hame's aye hame, as the Devil said when he found himself in the Court of Session". And I have heard the Latin tag nemo repente fuit turpissimus - "no one becomes very bad all at once" - translated, "It takes five years to become a solicitor". Gentlemen, just as hypocrisy is the tribute which vice pays to virtue, so I regard this popular ribaldry as the tribute which folly pays to wisdom.

I have had many professions, but there is none for which I have a higher regard than the Law. For one thing I do not think any profession has ever excelled ours i n its strict standard of honour. I do not think there is any profession, too, so free from petty jealousy, or so ready to admire proved ability. And in these days there are few professions more difficult. Without doubt our bodies are fearfully and wonderfully made, and the doctors have an intricate task; and theological questions do not get easier as time goes on; and the parsons have a difficult task. But I am very sure that no other profession has harder problems than ours. We have to face the eternal paradox - that laws are made in their final form by Parliaments and Congresses - that is, by people notoriously incompetent for the task. As a result experts have to spend their lives

page_0003

3·

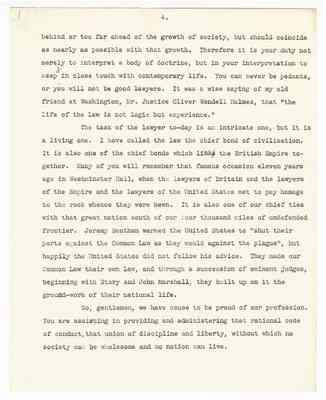

interpreting them. This task does not grow easier in these days of superabundant legislation, when the lawyer has usually to clear up the mess that the politicians make. Today, I fear, too many modern Acts of Parliament, at least in Britain, have, as someone has said, all the appearance of lucidity and all the reality of confusion. Well, a tough job keeps a man young and keeps his mind active. I am always struck with the enduring vitality of lawyers, and that is one reason why I say that in coming among you I am renewing my youth.

But, Gentlemen, we have one great consolation. I have heard an atheist defined as a man who had no invisible means of support. You have always an invisible means of support in the reflection that the law which you interpret is, with all its imperfections, the true cement of civilisation. Here in Canada, as in England, as in the United States, we have as a precious heritage that body of customs and principles which we know as the Common Law. Like the British Constitution, it is an organic thing, the growth of which never ceases. Like the British Constitution, too, it is largely unwritten. Blackstone's great work is an essay on the subject rather than a digest. It is your business not only to interpret that body of doctrine, but to enlarge it and to adapt it to the needs of a changing world. Law, I think, should be regarded as an elastic tissue which clothes a growing body. That tissue, that garment, must fit exactly. If it is too tight it will split, and you will have revolutmon and lawlessness, as we have seen at various times in our history when the law was allowed to become a strait-waistcoat. If it is too loose it will trip us up and impede our movements. Law, therefore, should not be too far

page_0004

4.

behind or too far ahead of the growth of society, but should coincide as nearly as possible with that growth. Therefore it is your duty not merely to interpret a body of doctrine, but in your interpretation to keep it in close touch with contemporary life. You can never be pedants, or you will not be good lawyers. It was a wise saying of my old friend at Washington, Mr. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, that "the life of the law is not logic but experience."

The task of the lawyer today is an intricate one, but it is a living one. I have called the law the chief bond of civilisation. It is also one of the chief bonds which link the British Empire together. Many of you will remember that famous occasion eleven years ago in Westminster Hall, when the lawyers of Britain and the lawyers of the Empire and the lawyers of the United States met to pay homage to the rock whence they were hewn. It is also one of our chief ties with that great nation south of our four thousand miles of undefended frontier. Jeremy Bentham warned the United States to "shut their ports against the Common Law as they would against the plague", but happily the United States did not follow his advice. They made our Common Law their own law, and through a succession of eminent judges, beginning with Story and John Marshall, they built up on it the groundwork of their national life.

So, gentlemen, we have cause to be proud of our profession. You are assisting in providing and administering that rational code of conduct, that union of discipline and liberty, without which no society can be wholesome and no nation can live.