Pages

page_0001

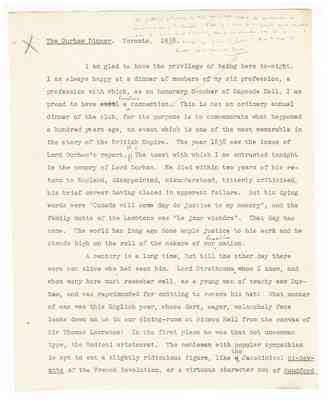

The Durham Dinner. Toronto, 1938.

I am glad to have the privilege of being here to-night. I am always happy at a dinner of members of my old profession, a profession with which, as an honorary Bencher of Osgoode Hall, I am proud to have a Canadian connection. [ST: hand written insert not legible]. This is not an ordinary annual dinner of the club, for its purpose is to commemorate what happened a hundred years ago, an event which is one of the most memorable in the story of the British Empire. The year 1838 saw the issue of Lord Durham's report.

The toast with which I am entrusted tonight is the memory of Lord Durham. He died within two years of his return to England, disappointed, misunderstood, bitterly criticised 1 his brief career having closed in apparent failure. But his dying words were "Canada will some day do justice to my memory'', and the family motto of the Lambtons was "Le jour viendra". That day has come. The world has tong ago done ample justice to his work and he stands high on the roll of the makers of our Canadian nation.

A century is a long time, but till the other day there were men alive who had seen him. Lord Strathcona whom I knew, and whom many here must remember well 1 as a young man of twenty saw Durham, and was reprimanded for omitting to remove his hat! What manner of man was this English peer, whose dark, eager, melancholy face looks down on us in our dining-room at Rideau Hall from the canvas of Sir Thomas Lawrence? In the first place he was that not uncommon type, the Radical aristocrat. The nobleman with popular sympathies is apt to cut a slightly ridiculous figure, like the Jacobinical ci-devants of the French Revolution, or a virtuous character out of Sandford

page_0002

2.

and Merton. The world, remembering the Rockinghams and Lafayettes of history, suspects a lack of humour and of common humanity. I remember Lord Rosebery once telling me that, in his early days, when he was Mr. Gladstone's chief lieutenant and the apostle of Scottish Liberalism , he was always in terror of being tarred with that brush. The reason is plain; such a type is apt to be condescending, and democracy has no use for condescension. Durham's political creed was mainly a family bequest and not very suited to his temperament. He was called "Radical Jack" and "The King of the Colliers," but I wonder how much he really understood that fine stock, the Durham miners! He was their master, and their patron; I doubt if he could ever have been their comrade and friend. But he had one truly Liberal quality; he hated cruelty and tyranny of any kind; and he was as vehement a critic of the brutality and intimidation of the miners' unions as of the misdeeds of Tory landlords.

What was the nature of the man? There i s not much to attract us in the malicious picture drawn by Charles Greville. He was full of class pride and had a good deal of personal vanity. He was q uick-tempered, intolerant, suspicious, always a difficult colleague. The fact is that he had been badly spoilt by home indulgence in his youth. He was capable of deep affection, as the beautiful letters to his wife and children show, but that affection was largely confined to his family circle. To the world at large he presented a cold, aloof demeanour, varied by sudden fits of passion. There was something febrile in his nature, as in Canning's, which was not altogether due to his wretched health. He was respected and feared, but not gener[ally]

page_0003

[gener]ally liked. It might have been said of him, as was said of an English statesman of our own day - he had not an enemy in the world, but he was cordially disliked by his many f riends.

In politics he was an unreliable colleague, which was a fault, but as was shown by his friendship with Canning, he was no narrow party man - which we must count as a merit. He was a genuine reformer and compelled the Whigs to extend their reforming zeal to more vital things than the franchise. Here is his own statement of his creed.

"I do not wish new institutions but to preserve and strengthen the old. Some would confine the advantages of those institutions to as small a class as possible, I would throw them open to all who have the ability to comprehend them and the vigour to protect them. Others again would annihilate them for the purpose of forming new ones on fanciful and untried principles. I would not only preserve them, but increase their efficiency and add to the number of their supporters."

If he had been sitting in the British Parliament today I fancy he would have allied himself to our younger Conservatives. In his own day he may be said to have lacked what Cavour called the tact des chose possibles.

He was magnificent in generalities but somewhat maladroit in tactics. No one ever questioned his courage. The man who, sick and weary, undertook at short notice the mission to Canada had a very stout heart.

About his abilities it is hard to decide. He had a great gift of somewhat florid torrential oratory, but that is no uncommon thing. He had foresight, too, and imagination beyond most of his

page_0004

4.

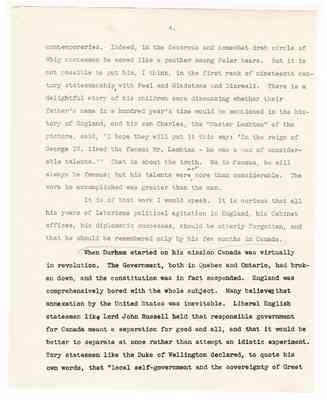

contemporaries. Indeed, in the decorous and somewhat drab circle of Whig statesmen he moved like a panther among Polar bears. But it is not possible to put him, I think, in the first rank of nineteenth century statesmanship with Peel and Gladstone and Disraeli. There is a delightful story of his children once discussing whether their father's name in a hundred year's time would be mentioned in the history of England, and his son Charles, the "Master Lambton" of the picture, said, "I hope they will put it this way: 'In the reign of George IV. lived the f'amous Mr . Lambton - he was a man of considerable talents.' " That is about the truth. He is famous, he will always be famous; but his talents were not more than considerable. The work he accomplished was greater than the man.

It is of that work I would speak. It is curious that all his years of laborious political agitation in England, his Cabinet offices, his diplomatic successes, should be utterly forgotten, and that he should be remembered only by his few months in Canada. When Durham started on his mission Canada was virtually in revolution. The Government, both in Quebec and Ontario, had broken down, and the constitution was in fact suspended. England was comprehensively bored with the whole subject. Many believed that annexation by the United States was inevitable. Liberal English statesmen like Lord John Russell held that responsible government for Canada meant a separation for good and all, and that it would be better to separate at once rather than attempt an idiotic experiment. Tory statesmen like the Duke of Wellington declared, to quote his own words, that "local self-government and the sovereignty of Great

page_0005

5.

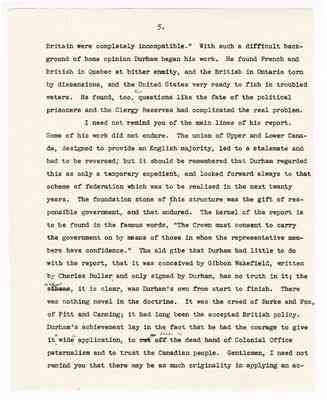

Britain were completely incompatible." With such a difficult background of home opinion Durham began his work. He found French and British in Quebec at bitter enmity, and the British in Ontario torn by dissensions, and the United States very ready to fish in troubled waters. He found, too, that questions like the fate of the political prisoners and the Clergy Reserves had complicated the real problem.

I need not remind you of the main lines of his report. Some of his work did not endure. The union of Upper and Lower Canada, designed to provide an English majority, led to a stalemate and had to be reversed; but it should be remembered that Durham regarded this as only a temporary expedient, and looked forward always to that scheme of federation which was to be realised in the next twenty years. The foundation stone of his structure was the gift of responsible government, and that endured. The kernel of the report is to be found in the famous words, "The Crown must consent to carry the government on by means of those in whom the representative members have confidence." The old gibe that Durham had little to do with the report, that it was conceived by Gibbon Wakefield, written by Charles Buller, and only signed by Durham, has no truth in it; the report, it is clear, was Durham's own from start to finish. There was nothing novel in the doctrine. It was the creed of Burke and Fox, of Pitt and Canning; it had long been the accepted British policy. Durham's achievement lay in the fact that he had the courage to give it a wider application, to shake off the dead hand of Colonial Office paternalism and to trust the Canadian people. Gentlemen, I need not remind you that there may be as much orginality in applying an ac