Pages

page_0001

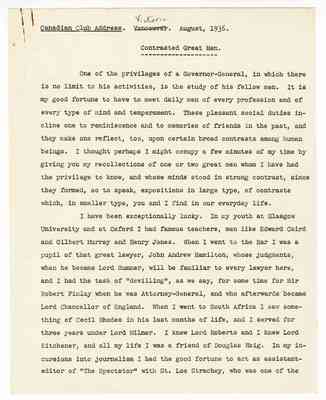

Canadian Club Address. Victoria, August 1936.

Contrasted Great Men.

One of the privileges of a Governor-General, in which there is no limit to his activities, is the study of his fellow men. It is my good fortune to have to meet daily men of every profession and of every type of mind and temperament. These pleasant social duties incline one to reminiscence and to memories of friends in the past, and they make one reflect, too, upon certain broad contrasts among human beings. I thought perhaps I might occupy a few minutes of my time by giving you my recollections of one or two great men whom I have had the privilege to know, and whose minds stood in strong contrast, since they formed, so to speak, expositions in large type, of contrasts which, in smaller type, you and I find in our everyday life.

I have been exceptionally lucky. In my youth at Glasgow University and at Oxford I had famous teachers, men like Edward Caird and Gilbert Murray and Henry Jones. When I went to the Bar I was a pupil of that great lawyer, John Andrew Hamilton, whose judgments, when he became Lord Sumner, will be familiar to every lawyer here, and I had the task of "devilling", as we say, for some time for Sir Robert Finlay when he was Attorney-General, and who afterwards became Lord Chancellor of England. When I went to South Africa I saw something of Cecil Rhodes in his last months of life, and I served for three years under Lord Milner. I knew Lord Roberts and I knew Lord Kitchener, and all my life I was a friend of Douglas Haig. In my incursions into journalism I had the good fortune to act as assistant editor of "The Spectator" with St. Loe Strachey, who was one of the

page_0002

2.

greatest British journalists of his day. Among men of letters I spent two Sundays with George Meredith, and I knew Thomas Hardy intimately; while Sir James Barrie and Rudyard Kipling were friends from my youth. I had the good fortune also to know Lord Cromer, the maker of modern Egypt, and received from him many lessons in public administration which I have never forgotten.

Then during my year in business and in politics I knew fairly intimately the leaders of every political party at home, since I was always rather loose in my party attachments, and I had the uncommon good fortune to see something of great Imperial statesmen, like Sir Wilfrid Laurier and General Botha and General Smuts. I do not think there can be any better luck for a man than to have seen a good deal of people who were enormously his superior in intellect and character. It keeps him humble; he is not apt to rate his own modest capacities too high.

On looking back it seems to me that among these friends of mine there was a recurrent contrast in types. There was the man of great ability who had the power of expressing himself with complete accuracy and fulness whenever he so desired, and joined with this gift was the capacity also to make people realise his personality, to get himself, so to speak, across the footlights and become known to millions who never saw him in the flesh. And there was the other type, who were fully as able and as wise, but who were not explicit, who required a great deal of knowing before their qualities could be understood, and who, therefore, could never become, except by an accident, dominating personalities in the public mind. The ordinary

page_0003

3·

man might respect such men for their deeds, but he never got to know them.

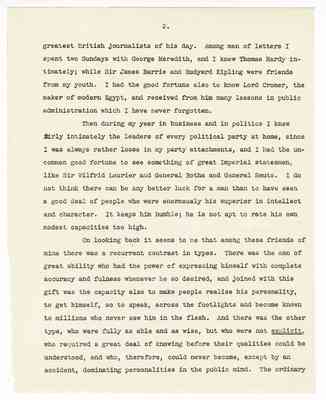

The first two examples I will take are Mr. Lloyd George and my old chief, Lord Milner. Mr. Lloyd George has the most perfect gift of expressing himself and his personality of any man I have ever known. That is why he has been so great a popular leader - he is wholly comprehensible. No atmosphere of mystery ever surrounded his character or his talents, and the plain man found in him something which he could himself assess, so that he could give or withhold his confidence as if he were dealing with a familiar friend. This power of inducing a sense of intimacy among millions who have never seen his face is the greatest of assets for a democratic statesman.

Mr. Lloyd George in the War was a living figure everywhere, not only for Britain but for all the world. He was like an electric current whose strength is scarcely lessened by transmission over distances. He used a universal tongue, and his strength lay in this universality, this abounding share in a common humanity. That is what made him, I think, the supreme civilian figure in the War.

He had a mind which was immensely quick and receptive, but not very retentive. He could pick up an idea and use it brilliantly, and then forget it completely. This made him a difficult man to serve. But it also gave him his perpetual exuberance and vigour. He could never be stale because he could get rid of all unnecessary baggage and wake every morning to a new world. You can realise how magnificent a leader he was in a time like war, when things were perpetually changing.

page_0004

4.

This power of comprehensibility was shared, I think, by our late beloved King. He had that simplicity and goodness which every man of every nation could understand who was brought into contact with it. Modern inventions like the Wireless made that contact possible. He appealed to the common denominator in human nature everywhere. When I am inclined to be pessimistic about the future I always console myself by thinking of what King George meant to the world, and the immense power which dutifulness and kindness can have over the hearts and imagination of mankind.

My old chief, Lord Milner, was exactly the opposite. His mind was in some ways the keenest weapon I have ever known. He had superb powers of insight and comprehension, as well as a character in the highest degree noble and disinterested, and the most inflexible courage. But he had none of the gifts of a popular leader. He had a personality, the quality of which could not be readily communicated to the ordinary man. One had to penetrate into the secluded chambers of his intellect before one realised his greatness. He was the kindest of men, but he had no gift of laying himself alongside of other people, and consequently there were large sections of his fellows whom he never understood, and who did not understand him. His great chance came in the l ast years of the War, when he became War Minister. When the history of the War Cabinet comes to be fully written it will be seen that almost all the heaviest executive work was done by him. I remember well how Mr. Lloyd George was constantly referring intricate matters to him and leaving them to be dealt with at his discretion. But how many people in Britain and the world realised this? To his countrymen, even to the very end, Lord Milner

page_0005

5.

remained the "great unknown."

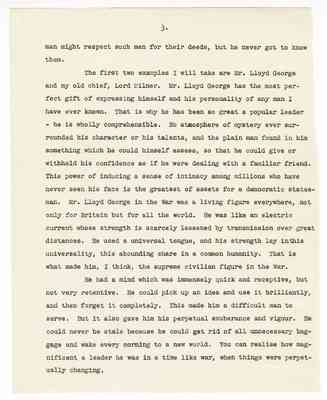

I will take another pair: this time soldiers. First of all Lord Haig. Mr. Duff Cooper's Life will, I hope, meke people understand something o:f a most remarkable figure. Those who thought Haig a commonplace type, who attained a great position by good luck, were wildly wrong. He was a member of my old College at Oxford, and a neighbour in Scotland, and I think I may say I knew him as well as anybody. I watched his extraordinary career from the brilliant poloplaying cavalry soldier to the silent, preoccupied commander of great armies. He cast back to an ancestral Scottish type about the age of fifty, and religion began to play a very large part in his life. The fashionable cavalry soldier became something very like a Scottish Covenanter. He was quite incapable of expressing himself in speech, except at a military conference. He wrote brilliantly, for every sentence hit you between the eyes; but he had no small talk, and even in serious discussions he found it very difficult to state his views. The consequence was that Haig never became an intelligible and popular figure to the ordinary soldier, as Lord Roberts did. His achievements made them respect him profoundly, and his fight for their rights after the War earned him their undying gratitude. When he died, and his body was brought in the winter midnight to Edinburgh, the streets of the Scottish capital were crowded with hundreds of thousands of his old troops. But I do not feel that the man Douglas Haig was ever quite realised by anybody but his most intimate friends.

As a complete contrast I would take Sir Henry Wilson. His