Pages

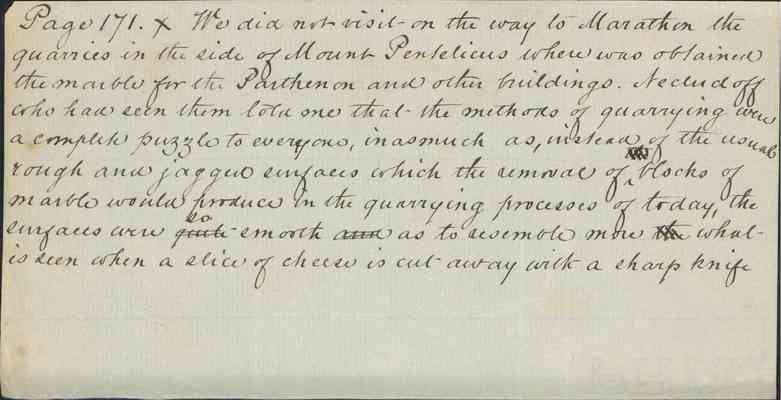

Page 171. X We did not visit on the way to Marathon the quarries in the side of Mount Pentelicus where was obtained the marble for the Parthenon and other buildings. Necludoff who had seen them told me that the methods of quarrying were a complete puzzle to everyone, inasmuch as, instead of the usual rough and jagged surfaces which the removal of blocks of marble would produce in the quarrying processes of today, the surfaces were quite so smooth and as to resemble more the what is seen when a slice of cheese is cut away with a sharp knife

171 the course of the next morning. At the hotel we found the boarders anxiously expecting us and fearful lest something had befallen us. X

Before leaving the city I was taken by M Necludoff to a reception at the Russian Minister’s whose name was [Persiani?]. I have already described explained that his ancestor had entered the Russian diplomatic service by the father having been employed as a dragoman or interpreter at Constantinople. His name was very unRussian in sound. He was an easy mannered gentleman and both his wife and himself spoke with pleasure and even gratitude of their reception on board an American war vessel which had been in the Piraeus a few weeks before when Mr Pryor was there. What particularly delighted them was that upon reaching the deck the Russian flag was hoisted to one of the masts and saluted with a discharge of cannon, all in the sight of the English and French vessels who could not prevent it. That flag has not been seen in those waters for over a year, and the ignorant Greeks concluded that Russia has found an ally in the Americans.

At length after a fortnight’s stay in Athens I bade my friends adieu and started in another of the Austrian Lloyds for Constantinople and Syra and Smyrna. Mr Hill gave me before I left a letter of introduction to Admiral Lyons who commanded the British fleet before Sebastopol. The way in which he had become sufficiently well acquainted with him to do this was follows. When young prince Otto of Bavaria had been chosen to rule over the new kingdom, he embarked in an English frigate at Trieste on his way to Athens, which was commanded by Capt Lyons. The Captain made himself very agreeable to the youthful king, and the latter was so much pleased with him that he requested the English government to allow him to remain in Greece as their diplomatic representative. The government consented to this and during the many years that Minister Lyons was at Athens Mr Hill and himself became very intimate, and it was therefore a perfectly natural proceeding, with no presuming upon an acquaintanship for him to give me the letter. While Minister Lyons was at Athens, the eldest son of the then Duke of Norfolk, who was inclined to be dissipated, arrived then, consigned to his care. He was received in the Minister’s family and soon after became engaged to one of his daughters whom he married. It was a brilliant marriage for the young woman for she in a few years became the duchess of Norfolk herself. Her husband did not live long however, and she was soon a dowager. The alliance was an advantageous one for the Lyons family in several ways, for, although the Duke of Norfolk of today is not the influential nobleman that his ancestors were, it brought them before the public, and the admiral’s son, who became in time ambassador to Paris, retaining the post for many years, was probably assisted in his first steps upwards by the influences of the Howard connection.

It can be seen that Mr Hill as a missionary was quite an exception. When I knew him he never troubled himself about the kind of work that the good people at home who provide the money presumed that he was busy about, and yet he was universally respected and retained the confidence

172.

of the Board of Foreign Missions to the last. He lived to an advanced age and he made a last visit to America in a year that a general convention of the Episcopal Church met either in Philadelphia or New York. This was about 1870. During some public proceedings of the two Houses it was announced that that veteran missionary the Rev Mr Hill was present, either on the platform of a hall or in the chancel of a church, and being too old and weak to address the audience he stepped forward so as to be well seen by everyone. He was well received by the assembled people, which proved how generally he was known.

The steamer left the Piraeus in the course of the afternoon and the next morning early we were at anchor before the town of Syra, the principal city of the island of the same name. It belonged to Greece, and since it has been wrested from Turkish rule, had become an important point on the highway to Constantinople. The town was a curious one to observe from our anchorage, as it consisted of a group of houses occupying the top of a cone-shaped hill and a vacant space between these and the new town below on the edge of the water. The explanation of this unbuilt space was that during the existence of piracy in the Egean Sea, which had lasted until those waters became frequented by the allied fleets of France and England engaged in the war with Russia, it was unsafe for a city to be located near the water; hence the position of the old city on the top of a hill. When possession became vested in the Greek government, it was sufficiently powerful to keep off the sea rovers, although they still abounded and continued to depredate upon the islands which Turkey retained, and then it became safe for business houses and other buildings required by the commerce of the place to be erected lower down.

After Syra we steamed direct for Smyrna which we reached in a few hours and where we remained at anchor for 24 hours. I went on shore but did not remain long, as the town consisted of a labyrinth of muddy alleys which made my first view of a Turkish city somewhat unprepossessing. I saw too for the first time a veiled woman after the Eastern fashion, and on the steamer there were already mussulmen of both sexes, the first class passengers of whom went through their devotions regularly at stated hours during the day and on the upper deck using the well known eastern rug for the purpose, upon which they knelt and bowed their foreheads to the floor. As new passengers came on board bound for Constantinople I conversed with several at meals. One of them, a Sardinian by birth, but who had lived in the Levant for years, had been in Smyrna when Kosta was rescued from the Austrian frigate by Capt Ingraham, in command of a little American sloop of war. It is an historical event which occurred about the year 1850, and need not be detailed here. Austria was cordially defeated by all of the nationalities bordering upon the eastern Meditterranean, and when the frigate was bullied into surrendering a prisoner by a much smaller vessel which moved to a position very close to her, intending to shoot if refusal was persisted in, great was

173

the joy of all the Greeks and Italians of Smyrnas, as well perhaps of those Turks who were able to discern any meaning in the incident. My newly made friend took pleasures in bearing witness to the satisfaction which this humiliation of Austria produced. I inquired after dried figs when on show but was told that they were scares and of inferior quality. The crop is bought up by English and other foreign dealers and Smyrna figs can be found more easily in London and Paris than in the locality of their curing. During the harvest, in June, there is great activity; large quantities of the fruit arriving daily on the backs of dromedaries, and a large number of persons find profitable employment for weeks attending to the washing, drying and packing.

We left Smyrna towards sunset of our second day with the weather looking stormy. During the night a regular gale began to blow and there was some uneasiness among the lady passengers. The steamer took refuge however behind a headland not far from the entrance to the Dardanelles where we remained all the next day, quite near a little Turkish town. Among the other passengers taken in at Smyrna was a Capt Chads of the English heavy artillery, a nephew of an Admiral of the same name commanding the Baltic fleet. I had several pleasant conversations with him and found him quite companionable. At night in the cabin several round games were organised by the gentlemen in which the ladies took part, and altogether our evening was profitably spent.

While at Smyrna there was anchored near us three superb English ships-of-the-Line or Line-of-battle-ships.-the Hannibal, Princess Royal and St Jean d’Acre, which were on their way to Malta for the winter. They were not quite the largest ships in their navy, being only three-deckers. Two other ships of the same class but having 4 decks had lately been built; the Royal Albert and Duke of Wellington, both of which were in the Black Sea, the former being the flagships of Admiral Lyons. A ball was given on board of one of these ships the night that we were near by, and I should have liked very much to have been able to attend. I mentioned this to Capt Chads the next day and he told me how easy it would have been for him to procure an invitation for me, as he had been present himself.

The morning after remaining in safety from the gale behind the headland we were underway again and passing through the Dardanelles. The passage occupied the greater part of the day and there was nothing particularly attractive in the scenery on each side. The gale had lowered the temperatures to the freezing point and there were traces of snow on the hills around. The celebrated Castles of the Dardanelles were two large forts, one on each side, the passing between which caused some delay while certain formalities were being observed. In the course of the afternoon we entered the Sea of Marmara and stopped for some freight a nd passengers at a little town on the European show, called Gallipoli, which was one of the camping places of the British as their troops were being concentrated in Turkey for the war against Russia.

174.

During the day several of the passengers approached me to exchange a few words of conversation. They had found out that I was American and seemed desirous of knowing something about the great republic. My ability to speak in French made this quite easy, for it was in that language that we spoke. Capt Chads desired to join in the conversation several times as he heard us discussing the war and making remarks about England, which he desired to correct. But he could say only a few words in French, and was evidently mortified at his inability to set us right. Among my acquaintances thus made was an old gentleman who had a daughter with him. He was probably of the Greek faith, and had been in the service of the Sultan, but for some reason had been banished from Constantinople, and was returning from the direction of Trieste after an absence of two years. He was intelligent and well informed - spoke French fluently, and presented me with his card when we reached our journey’s end, inviting me at the same time to call and see him at some place outside of the city. The daughter, about 35, was also intelligent and educated. I should have liked to see them at their home, but the suburbs of Constantinople were too difficult to explore for me to attempt a visit. Dawn the next morning found us at anchor in the Bosphorus in front of Seraglio Point, and in full view of the wonderful sight which the city first offers to the stranger. There was a mist which gradually rose as the sun came into view, and slowly the mosques which are so conspicuous as parts of the city became clearly defined. Before leaving the steamer everything had become distinct, and the impression produced upon me as I gazed upon the wonderful beauty of this Turkish capital can never be effaced. The illusion however lasted but for a short time, as after reaching a so called custom-house at one of the landings of Pera, the European quarter, the fifth of every description and the narrow muddy alleys with hovels of every kind bordering them, which greeted us, made us realize that Constantinople was indeed a city of dirt and bad smells. I did not stop to moralise on the situation, but hurried on the hotel d’Angleterre where I had been advised to stop, as I would meet there a distinguished company of English officers. The hotel was quite full but I insisted on staying there, if only a closet were given me, and Madame Misirié, the wife of the landlord, who was a Greek, concluded to take me in and give me a good room as soon as one would be vacant.

At the breakfast table I found about a dozen persons seated, all men. They were mostly with full beards, fine specimens of manhood, and, as I found out afterwards, were mainly army officers, there being a few civilians, such as Queen’s messengers and officers among them. I found no one to talk to, but listened to what a group near the fire were saying. One of these I scraped acquaintance with afterwards. His name was Purdy, and he was a Queen’s messenger. These messengers were always educated persons, who carried important government dispatches. They were numerous during a war, but have been probably discontinued to some extent since the perfection of the telegraph system.

After breakfast, having requested the landlord to place me at dinner along side of some intelligent and conversable person, I started out on a sight