Pages That Need Review

Research Material for Speech- "The Broken Promise of 'Brown v Board of Education' ", 2004

30

Brown v. Board of Education Page 5 of 5

1996 Hopewood v. Texas: Fifth Circuit of the Court of Appeals rules that the affirmative action plans used by Tex unconstitutional; the Supreme Court refuses to review the case.

1999 Thirty years of court-supervised desegregation ends in Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Gratz v. Bollinger; Frutter v. Bollinger: The Supreme Court considers challenges to the University of Michigan's affirmative a undergraduate and law schools, respectively. LDF represents African-American and L intervenors in the Gratz undergraduate school case. A decision is expected in June o

http://www.brownmatters.org/chrono_detailed.html 1/17/2004

31

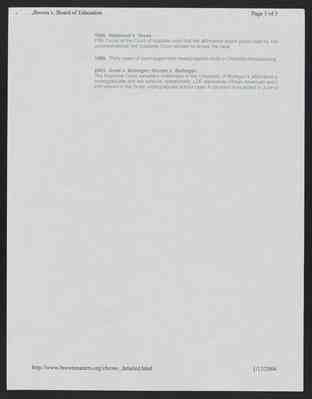

[image:] A black woman and child seated on the steps of a pillared government building. The woman holds a newspaper showing the headline "HIGH COURT BANS SEGREGATION IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS"

Dialogue on

Brown v. Board of Education

32

The Story of Brown v. Board of Education

May 17, 2004, is the fiftieth anniversary of the United States Supreme Court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The decision brought an end to the legal doctrine of "separate but equal," enshrined by the same court nearly sixty years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson. In Plessy, the Supreme Court held that segregation was acceptable if the separate facilities provided for blacks were equal to those provided for whites. The sole dissent came from Justice Harlan. Arguing that "our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens," Justice Harlan accurately predicted further "aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens."

[image:] Photograph of "Colored Waiting Room" sign with the following attribution: ©Bettmann/CORBIS; reprinted with permission.

Justice Harlan's warning was fully realized in the regime of "Jim Crow" laws that, with the Supreme Court's sanction, enforced segregation of blacks and other people of color from many of the facilities enjoyed by white citizens across much of the United States. Public schools, transportation facilities, residential neighborhoods, public and private theaters, restaurants, and even public lavatories and drinking fountains were designated for the exclusive use of "whites," while separate -- and supposedly equal -- facilities were set aside for "coloreds." Any hope of changing these laws through democratic processes was stripped away as states erected legal barriers to the exercise of the vote by black citizens. And in courthouses across the land, blacks were systematically excluded from service on juries.

Segregation was the law, but almost immediately it met with resistance. Less than fifteen years after Plessy, a group of individuals committed to fighting against the brutalities of Jim Crow America had formed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (the NAACP). And in 1926, Mordecai W. Johnson arrived as the first black president at all-black Howard University and put the institution on a crash course for academic excellence. In 1929, he hired Charles Hamilton Houston as dean of the Howard University Law School. The result of Houston's arrival and the changes he initiated was a law school curriculum taught by and capable of producing some of the greatest legal talents America has seen. Working individually and through the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund, these lawyers would change the course of American law and society.

This group of black attorneys included Houston himself, Robert L. Carter, William T. Coleman, William Henry Hastie, George Hayes, Oliver Hill, Constance Baker Motley, James M. Nabrit, Jr., Spottswood W. Robinson III, and -- perhaps most famous of all -- Thurgood Marshall. They were joined by others committed to the fight against segregation, including Jack Greenberg of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. In the decades leading up to Brown, these lawyers progressively chipped away at the legal structure fortifying segregation. All-white jury pools, covenants that restricted ownership of property in certain neighbors by race, laws disenfranchising black voters, and segregated graduate and professional schools were all challenged, often successfully. Attention then turned to the politically charged arena of public school segregation.

The legal strategy focused first on insisting that states take the Plessy standard seriously. "White" and "colored" schools were certainly separate, but in most cases they were far from equal. District by district, legal challenges were brought insisting that black schools be brought up to par with their "whites only" equivalents. This strategy, however, required fighting district by district and did not directly challenge the doctrine of "separate but equal." In 1950, the NAACP resolved that nothing other than education of all children on a nonsegregated basis would be an acceptable outcome. Work began on laying the final groundwork for Brown v. Board of Education.

The case known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas actually included appeals from decisions in four separate states: Kansas, Delaware, South Carolina, and Virginia. Each case represented individual acts of courage by families willing to face local resistance -- evan hostility -- to bring an end to segregation.

[image:] Photograph of black and white children standing together in a classroom with hands over their hearts looking at a flag raised by a young black boy. Includes the following attribution: © Bettmann/CORBIS; reprinted with permission.

Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education

1

33

School conditions in these four test cases varied, from stark differences in South Carolina between the "colored" and "white" schools to a closer parity in the Topeka, Kansas, schools. In all four states, however, the schools were segregated by law, and the NAACP's position was that equality could not be achieved until segregation was brought to an end.

Although the four decisions went against the NAACP in the trial courts, its position was strengthened by some of the decisions. In South Carolina, Judge Julius Waties Waring dissented from the opinion of his two colleagues who also heard the case, declaring that "segregation is per se inequality." And in Kansas, the three-judge panel attached to its opinion a finding of fact that segregation has a detrimental effect on colored children, especially when it is enforced by law.

The four cases were argued on appeal to the United States Supreme Court in 1952, with the issue being whether segregation depriced students of equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court requested reargument of the case in 1953. Before the reargument could occur, Chief Justice Vinson died and was replaced by Chief Justice Earl Warren. Under his guidance, a unanimous Court on May 17, 1954, issued its decision declaring that segregation of the public schools was unconstitutional. A landmark in the struggle for equality and under the law for all Americans had been achieved.

Starting the Dialogue

At the heart of Brown v. Board of Education was the desire to ensure equal protection of the laws for all Americans. The following questions ask students to reflect on what has been required -- and what has been achieved -- in pursuit of this goal in our nation's schools.

Dialogue leaders should feel free to develop their own lines of inquiry for exploring the significance of Brown v. Board of Education. Page 3-6 offer ideas for such topics as

• Issues of equality and racial diversity in America • The role of education in effecting social change • The legacy of segregation in the United States • The role of law in maintaining or changing the status quo

1. You are a classmate of Linda Brown at a segregated school in Topeka, Kansas, in 1951. She and her family have decided to challenge the idea that schools should be separated by race. Gaining admission to the "whites only" school may very well mean that members of your community will harass you and your family and that you will encounter hostility from your classmates and teachers at your new school.

Do you join Linda Brown?

2. The year is 1960. You are one of ten black students who have been admitted into a formerly "whites only" high school. In class, you struggle to get the teacher's attention to answer a question. At lunch, it is clear that you are not welcome to join most of the other students at their tables. When entering school, you often receive a glare or hear a muttered comment from parents dropping off their children.

How do you cope with life at your new school?

3. Abraham Lincoln High School is located in a community with high unemployment and low family incomes. Robert E. Lee High School is located in a prosperous community in the same state. Both Abraham Lincoln High and Robert E. Lee High receive the same amount of money per pupil from the state government. Robert E. Lee High, however, is able to collect substantially m ore local tax money from its residents and thus has significantly more money to spend on each pupil. It can attract the best teachers by offering high salaries, has a state-of-the-art computer center, and offers a wide range of courses in music and art. Abraham Lincoln High has to pay its teachers below the state average and loses many teachers each year when they leave for better paying jobs. It cannot afford even one computer per classroom. Because of budget constraints, courses in music and the arts have been eliminated. The school's athletic program is at risk of being cut.

Has the state met its obligation to provide an equal education to students at Abraham Lincoln High and Robert E. Lee High?

4. Imaging that you are a student at Robert E. Lee High School. You are told that, as a result of a new state law intended to equalize opportunity among the state's school districts, part of your school's funds must be shared with Abraham Lincoln High School. Budget cuts will mean that the school may lose its computer center and that the number of opportunities for participation in athletic, musical, and artistic events will be sharply reduced.

How do you respond?

5. You are a high school senior trying to decide where to attend college.

How important to you would it be to attend a racially diverse college? Should college be able to consider the race of applicants in trying to create a diverse student body? What should a racially diverse American college campus look like?

6. Think about the other students at your school, your circle of friends, and the people who live in your neighborhood.

To what extent do you think Brown v. Board of Education's dream of an integrated America has been made real?

ABA Division for Public Education

2

34

Exploring the Issues

The story of Brown v. Board of Education and its legacy raises a host of issues concerning American law and society. The following features offer opportunities to explore some of these issues with students. Each feature includes at least one "conversation starter" -- a brief excerpt from an essay or legal opinion, for example, or a political cartoon or photograph--that can easily be read in a few minutes. The conversation starters are followed by focus questions you can use to begin your dialogue with the students. Feel free to pick and choose among these topics -- or design your own -- according to your interests and the time you have available with the students.

What is Equality Under the Law?

I. Declaration of Independence, 1776

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.

II. Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the question before the Supreme Court was whether a Louisiana law providing for separate railway cars for whites and blacks violated the Constitution.

The object of the [Fourteenth] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality . . . If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane. -- Justice Henry Billings Brown, majority opinion

Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. -- Justice John Marshall Harlan, dissenting

III. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. -- Chief Justice Earl Warren, for a unanimous Court

IV. Grutter v. Bollinger, No. 02-241 (2003)

The issue before the Court in Grutter v. Bollinger was whether the University of Michigan Law School could use race as a consideration in admitting students.

Government may treat people differently because of their race only for the most compelling reasons . . . Today we endorse [the] view that student body diversity is a compelling state interest that can justify the use of race in university admissions. -- Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, majority opinion

[R]acial classifications are per se harmful and . . . almost no amount of benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify such classifications. -- Justice Clarence Thomas, dissenting

Focus Questions

1. What does "created equal" mean to you? People are obviously very different, so what, exactly, do we mean by "equality"? Equality of opportunity? Equal treatment under law? Equal treatment for similarly situated individuals?

2. The doctrine of "separate but equal" upheld in Plessy put African Americans at a severe disadvantage. The practice upheld in Grutter gave African Americans and members of certain other minorities an advantage in the law school's admission policy.

The dissents in both cases essentially argued that the Constitution is color-blind. What does that mean? Is the Constitution color-blind? Should it be?

3. How should we deal with the possible harm to some individuals caused by preference established to advance the interests of members of historically disadvantaged groups? Does the "benign" intention of the preference make a difference?

Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education

3

35

Should Schools Serve as Laboratories for Social Change?

I. Brown v. Board of Education (II), 349 U.S. (1955)

The unanimous Brown decision in 1954 didn't specify how (or how quickly) desegregation was to be achieved in the thousands of segregated school systems. The case was reargued on the question of relief, and on May 31, 1955 (almost exactly one year after the first decision), the Court issued an opinion, commonly referred to as Brown II.

The NAACP urged desegregation to proceed immediately, or at least within firm deadlines. The states claimed both were impracticable. The Court, fearful of hostility or even violence if the NAACP views were adopted, embraced a view close to that of the states. . . . [e]ssentially return[ing] the problem to the courts where the cases began for appropriate desegregative relief -- with . . . "all deliberate speed." . . . By 1964, a decade after the first decision, less than 2 percent of formerly segregated school districts had experienced any desegregation. -- Dennis J. Hutchinson, "Brown v. Board of Education," in the Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States

[image:] Cartoon showing a man (labeled "SOUTH") using a horse (labeled "GRADUALISM") to plow a field (labeled "STEADY PROGRESS IN RACE RELATIONS"). Another man comes from behind him leading a horse while saying, "YOU'RE NOT GOING FAST ENOUGH -- TRY THIS ONE." The Cartoon is captioned: "No job for a race horse." Attributed to John Kennedy, May 22, 1954, Arkansas Democrat. Reprinted with permission of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette

II. Little Rock Central High School, 1957

Little Rock Central High School was supposed to be desegregated by the beginning of the 1957 school year. On September 2, the night before the first day of school, Governor Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to monitor the school. The next day, the Guardsmen prevented nine black children from entering the school. On September 20, a Federal District Court issued an injunction that prevented Governor Faubus from using the National Guard to deny the students admittance to Central High. When the nine students returned to the school, however, police removed them for their own protection after a mob of 1,000 people around the school grew unruly. President Eisenhower intervened, sending 1,000 paratroops and 10,000 National Guardsmen to Little Rock. The Little Rock Central High School was finally desegregated on September 25, 1957.

Looking back on this year will probably be with regret that integration could have been accomplished peacefully, without incident, without publicity. -- Georgia Dortch and Jane Emery, co-editors of The Tiger (Little Rock Central High student newspaper), October 3, 1957

Focus Questions

1. Reaction to the first Brown decision was fierce in the Southern states, with newspaper editorials predicting violence and political leaders promising defiance. How do you think the Court's ruling for desegregation with "all deliberate speed" should have been interpreted? Do you think it gave too much deference to white resistance in the South? What do you think the result would have been had the Court demanded immediate desegregation? What would you have done as a justice in the same situation?

2. What can the Supreme Court do to enforce its decisions? What is the role of the other branches in enforcing Court decisions? What can the Court do without the full support of the other branches?

3. Why do you think schools were the focus of the litigation that led to the decision in Brown v. Board? Is it more important for schools to be diverse and desegregated than the rest of society?

4. What do you think are the possible problems and risks involved in using schools as the site of social reform?

5. Statistics show that schools that once were segregated by law have often "resegregated," not as a result of law but of housing patterns and other circumstances. Is the "voluntary" resegregation of our nation's schools harmful? In terms of effect on students, is there a difference between legally m andated segregation and segregation due to other factors? What should national, state, or local governments do about this issue?

ABA Division for Public Education

4

36

What Was the Impact of Segregation Beyond the Black Community?

In Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927), the United States Supreme Court held that Martha Lum, a Chinese girl living in Mississippi, had no right to an education in a "whites only" public school if a "colored" public school was available to her.

The Legislature is not compelled to provide separate schools for each of the colored races, and unless and until it does provide such schools, and provide for segregation of the other races, such races are entitled to have the benefit of the colored public schools. . . . If the plaintiff desires, she may attend the colored public schools of her district, or, if she does not desire, she may go to a private school. . . . But plaintiff is not entitled to attend a white public school. -- Excerpt from the Mississippi Supreme Court decision upheld in Gong Lum v. Rice

[image:] Photograph of a woman pointing to a large sign hanging above the porch of a home. The sign read: "JAPS KEEP MOVING THIS IS A WHITE MANS NEIGHBORHOOD." Caption: Hollywood, Los Angeles, California, 1923 © Bettmann/CORBIS; reprinted with permission

Focus Questions

1. Many groups in America have faced discrimination for their racial, ethnic, or religious identities. What is the difference between discrimination by private individuals or organizations and segregation enforced by law?

2. Suppose that the education offered at the "colored school" nearest Martha Lum's home had been equal to that offered at the "whites only" school in terms of quantifiable factors (books, physical facilities, teachers, etc.). What harm would Martha Lum have suffered by being denied admission to the "whites only" school?

3. What is the relationship between groups who were subject to official segregation in the years preceding the decision in Brown v. Board and groups who are included in affirmative action policies today? What consequences of segregation are affirmative action policies intended to remedy? When do you think such policies will no longer be necessary?

What Are Acceptable Preferences in College Admissions?

[I]n the national debate on racial discrimination in higher education admissions, much has been made of the fact that elite institutions utilize a so-called "legacy" preference to give the children of alumni an advantage in admissions. . . . The Equal Protection Clause does not, however, prohibit the use of unseemly legacy preferences or many other kinds of arbitrary admissions procedures. What the Equal Protection Clause does prohibit are classifications made on the basis of race. So while legacy preferences can stand under the Constitution, racial discrimination cannot. -- Justice Clarence Thomas, dissenting in Grutter v. Bollinger, No. 02-241 (2003)

Focus Questions

1. Justice Thomas mentions "many other kinds of arbitrary admissions procedures." These include preferences granted to • children of alumni ("legacies") • athletes • students with certain special skills (isncluding musical ability and artistic talent) • students from other parts of the country, and from rural areas Why do you think colleges might favor such students?

2. The majority in this case held that the use of race in admissions decisions was permitted under the Equal Protection Clause where the policy resulted in the kinds of educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body. What other kinds of preferences in admissions decisions could be justified on the same basis?

3. How do you think higher education in America would be different if the legislature enacted laws banning legacy preferences and other kinds of preferences? What could be done to make the higher education admissions process become a true meritocracy?

Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education

5

37

Who Is Guilty for the Harms of Slavery and Segregation?

The islands from Charleston, south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. Johns river, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States. -- Special Field Order No. 15, Major General W. T. Sherman, January 15, 1865

[image:] Cartoon with the following caption. Thomas Nast, "Andrew Johnson Kicking Freedmen's Bureau," Harper's Weekly, April 14, 1866, page 232. Reprinted with permission of HarpWeek,LLC

Focus Questions

1. Until the Civil War, slavery was legally permissible in much of the United States. The United States Supreme Court endorsed segregation laws until 1954. Is it justifiable to declare an individual or a society guilty for committing acts that were sanctioned by the government?

2. The United States has paid reparations to Japanese Americans confined to internment camps during the Second World War. Germany has paid reparations to survivors of the Holocaust. Should the descendents of slaves be paid reparations for the harms suffered by their ancestors? What about black Americans living today who suffered the impact of segregation firsthand? To what extent can monetary reparations compensate for past harm?

3. For some Americans, the phrase "forty acres and a mule" represents a promise broken by the United States government. Others note that General Sherman's order applied only during wartime and that President Johnson was never legally compelled to grant the land contemplated in the 1865 Freedmen's Bureau Act. What happens to property confiscated by the winning side in times of war? What do you think should have been done to the land confiscated from individuals who supported the Confederacy in the Civil War?

38

Participating in a Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education

Once of the hallmarks of a democracy is its citizens' willingness to express, defend, and perhaps reexamine their own opinions, while being respectful of the view of others. As you engage in your dialogue, here are some ground rules for ensuring a civil conversation:

■ Show respect for the views expressed by others, even if you strongly disagree.

■ Be brief in your comments so that all who wish to speak have a chance to express their views.

■ Direct your comments to the group as a whole rather than to any one individual.

■ Don't let disagreements or conflicting views become personal. Name-calling and shouting are not acceptable ways of conversing with others.

■ Let others exress their views without interruption. Your dialogue leader will try to give everyone a chance to speak or respond to someone else's comments.

■ Remember that a frank exchange of views can be fruitful as long as you observe the rules of civil conversation.

Note to Dialogue Leaders: Before beginning your dialogue, distribute these ground rules and review them with students.

The ABA Division for Public Education provides national leadership for law-related and civic education efforts in the United States, stimulating public awareness and dialogue about law and its role in society through our programs and resources and by fostering partnerships among bar associations, educational institutions, civic organizations, and others.

A .pdf version of the "Dialogue on Brown v. Board of Education" is available on the ABA Division for Public Education Web site at www.abanet.org/publiced.

The views expressed in this document have not been approved by the House of Delegates or the Board of Governors of the American Bar Association and, accordingly, should not be construed as representing the policy of the American Bar Association.

Design: mc2 communications

Cover photograph by Cass Gilbert, 1954; © Bettmann/CORBIS. Reprinted with permission.

Copyright © 2003 American Bar Association

[image:] Logo for "DIVISION FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION"

541 North Fairbanks Court Chicago, IL 60611 (312) 988-5735 Email: abapubed@abanet.org www.abanet.org/publiced

39

Data on African Americans from the Decennial Census

Cf. Brown when enforced

| Number of black | in 1960 | in 1970 | Increase from 1960 | Ratio 1970/1960 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawyers | 2180 | 3379 | 1199 | 1.6 |

| Doctors | 4706 | 11436 | 6730 | 2.4 |

| Policemen | 9391 | 23796 | 14405 | 2.5 |

| Electricians | 4978 | 14145 | 9167 | 2.8 |

| Bank Tellers | n/a | 10663 | ||

| Architects | 233 | 1258 | 1025 | 5.4 |

| Clergymen | 13955 | 13030 | -925 | 0.9 |

| College Professors | 5415 | 16810 | 11395 | 3.1 |

| Dentists | 1998 | 2098 | 100 | 1.1 |

| Social Workers | 14276 | 33869 | 19593 | 2.4 |

| Carpenters | 3672 | 44529 | 40857 | 12.1 |

| Teachers | 122163 | 223263 | 101100 | 1.8 |

| Social Scientists | 1069 | 3088 | 2019 | 2.9 |

| Pharmicists | 1069 | 3088 | 1039 | 1.7 |

| Nurses | 32034 | 62325 | 30291 | 1.9 |

Real wages for black women textile workers in South Carolina

| in 1960 | in 1970 | Increase from 1960 | Ratio 1970/1960 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average daily real wages | 9.5 | 13.5 | 4 | 1.4 |