Pages That Need Review

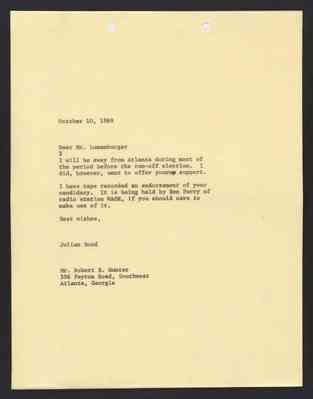

From Julian Bond to Mr. Luxemburger, 10 Oct 1969

1

October 10, 1969

Dear Mr. Luxemburger

3

I will be away from Atlanta during most of the period before the run-off election. I did, however, want to offer yourmy support.

I have tape recorded an endorsement of your candidacy. It is being held by Ben Perry of radio station WAOK, if you should care to make use of it.

Best wishes,

Julian Bond

Mr. Robert B. Hunter 306 Peyton Road, Southwest Atlanta, Georgia

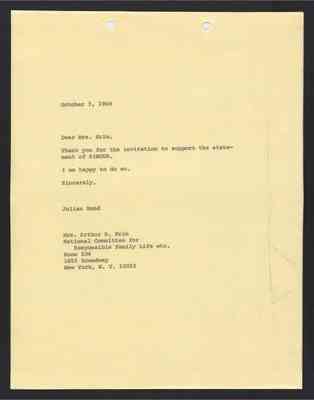

From Julian Bond to Mrs. Arthur Krim, 3 Oct 1969

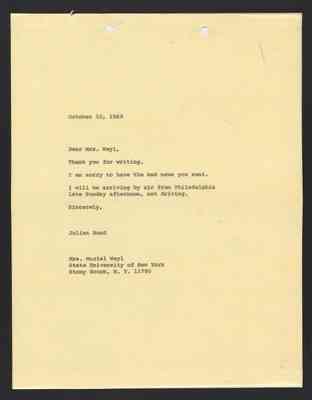

From Julian Bond to Muriel Weyl, 10 Oct 1969

1

October 10, 1969

Dear Mrs. Weyl,

Thank you for writing.

I am sorry to have the bad news you sent.

I will be arriving by air from Philadelphia late Sunday afternoon, not driving.

Sincerely,

Julian Bond

Mrs. Muriel Weyl State University of New York Stony Brook, N. Y. 11790

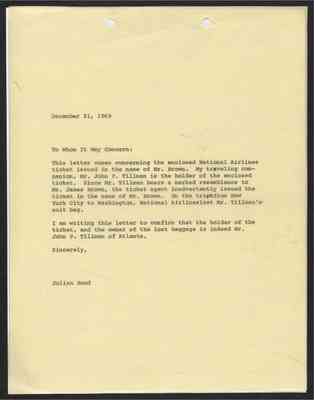

From Julian Bond to National Airlines concerning a lost bag, 31 Dec 1969

1

December 31, 1969

To Whom It May Concern:

This letter comes concerning the enclosed National Airlines ticket issued in the name of Mr. Brown. My traveling companion, Mr. John P. Tillman is the holder of the enclosed ticket. Since Mr. Tillman bears a marked resemblance to Mrs. James Brown, the ticket agent inadvertently issued the ticket in the name of Mr. Brown. On the trip from New York City to Washington, National Airlines lost Mr. Tillman's suit bag.

I am writing this letter to confirm that the holder of the ticket, and the owner of the lsot baggage is indeed Mr. John P. Tillman of Atlanta.

Sincerely,

Julian Bond

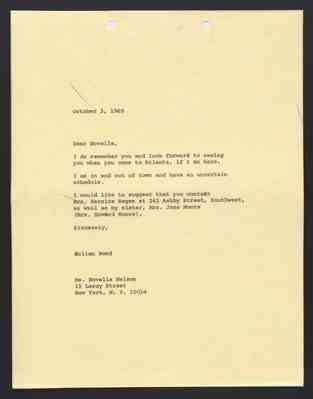

From Julian Bond to Novella Nelson, 3 Oct 1969

1

October 3, 1969

Dear Novella,

I do remember you and look forward to seeing you when you come to Atlanta, if I am here.

I am in and out of town and have an uncertain schedule.

I would like to suggest that you contact Mrs. Bernice Regan at 242 Ashby Street, Southwest, as well as my sister, Mrs. Jane Moore (Mrs. Howard Moore).

Sincerely,

Julian Bond

Ms. Novella Nelson 15 Leroy Street New York, N. Y. 10014

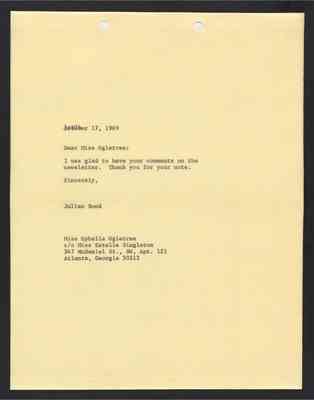

From Julian Bond to Ophelia Ogletree, 17 Oct 1969

Missouri v Jenkins (70-176)

83

142 MISSOURI v. JENKINS

SOUTER, J., dissenting

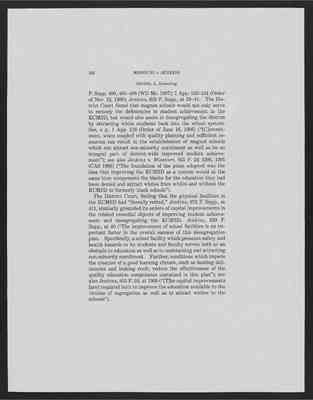

F. Supp. 400, 405-408 (WD Mo. 1987); 1 App. 133-134 (Order of Nov. 12, 1986); Jenkins, 639 F. Supp., at 39-41. The District Court found that magnet schools would not only serve to remedy the deficiencies in student achievement in the KCMSD, but would also assist in desegregating the district by attracting white students back into the school system. See, e.g., 1 App. 118 (Order of June 16, 1986) ("[C]ommitment, when coupled with quality planning and sufficient resources can result in the establishment of magnet schools which can attract non-minority enrollment as well as be an integral part of district-wide improved student achievement"); see also Jenkins v. Missouri, 855 F. 2d 1295, 1301 (CA8 1988) ("The foundation of the plans adopted was the idea that improving the KCMSD as a system would at the same time compensate the blacks for the education they had been denied and attract whites from within and without the KCMSD to formerly black schools").

The district Court, finding that the physical facilities in the KCMSD had "literally rotted," Jenkins, 672 f. Supp., at 411, similarly grounded its orders of capital improvements in the related remedial objects of improving student achievement and desegregating the KCMSD. Jenkins, 639 F. Supp., at 40 ("The imprvement of school facilities is an important factor in the overall success of this desegregtion plan. specifically, a school facility which presents safety and health hazards to its students and faculty serves both as an obstacle to education as well as to maintaining and attracting non-minority enrollment. Further, conditions which impede the creation of a good learning cliate, such as heating deficiencies and leaking roofs, reduce the effectiveness of the quality eduction components contained in this plan"); see also Jenkins, 855 F. 2d, at 1305 ("[T]he capital improvements (are) required both to improve the education available to the victims of segregation as well as to attract whites to the schools").

84

Cite as: 515 U.S. 70 (1995) 143

SOUTER, J., dissenting

As a final element of its remedy, in 1987 the District Court ordered funding for increases in teachers' salaries as a step toward raising the level of student achivement. "(I)t is essential that the KCMSD have sufficient revenues to fund an operating budget which can provide quality education, including a high quality faculty." Jenkins, 672 F. Supp., at 410. neither the State nor the KCMSD objected to increases in teachers' salaries as an element of the comprehensive remedy, or to this cost as an item in the desegregation budget.

In 1988, however, the State went to the Eighth Circuit with a broad challenge to the District Court's remedial concept of magnet schools and to its orders of capital improvements (though it did not appeal the salary order), arguing that the District Court had run afoul of Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) (Milliken I), by ordering an interdistrict remedy for an intradistrict violation. The Eighth Circuit rejected the State's position, Jenkins, 855 F. 2d 1295, and in 1989 the State petitioned for certiorari.

The State's petition presented two questions for review, one challenging the District Court's authority to order a property tax increse to fund its remedial program, the other going to the legitimacy of the magnet school concept at the very foundation of the Court's desegregation plan:

"For a purely intradistrict violation, the courts below have ordered remedies-costing hundreds of millions of dollars-with the stated goals of attracting more nonminority students to the school district and making programs and facilities comparable to those in neighboring districts....

"The questio(n) presented (is).... "...Whether a federal court, remedying an intradistrict violation under Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), may

85

144 MISSOURI v. JENKINS

SOUTER, J., dissenting

"a) impose a duty to attract additional non-minority students to a school district, and "b) required improvements to make the district schools comparable to those in surrounding districts." Pet. for Cert. in Missouri v. Jenkins, O.T. 1988, No. 88-1150, p.i.

We accepted the taxation question, and decided that while the District Court could not impose the tax measure itself, it could require the district to tax property at a rate adequate to fund its share of the costs of the desegregation remedy. Missouri v. Jenkins, 495 U.S. 33, 50-58 (1990). If we had accepted the State's broader, foundational question going to the magnet school concept, we could also have made an informed decision on whether that element of the District Court's remedial scheme was within the limits of the Court's equitable discretion in response to the constitutional violation found. Each party would have briefed the question fully and would have identified in some detail those items in the record bearing on it. But none of these things happened. Instead of accepting the foundational question in 1989, we denied certiorari on it. Missouri v. Jenkins, 490 U.S. 1034.

The State did not raise that question again when it returned to this Court with its 1994 petition for certiorari, which led to today's decision. Instead, the State presented, and we agreed to review, these two questions:

"1. Whether a remedial educational desegregation program providing greater educational opportunities to victims of past de jure segregation than provided anywhere else in the country nonetheless fails to satisfy the Fourteenth Amendment (thus precluding a finding of partial unitary status) solely because student achievement in the District, as measured by results on standardized test scores, has not risen to some unspecified level?

"2. Whether a federal court order granting salary increases to virtually every employee of a school district -

Missouri v Jenkins 2 (NOTE)

66

93-1823-CONCUR

18 MISSOURI v. JENKINS

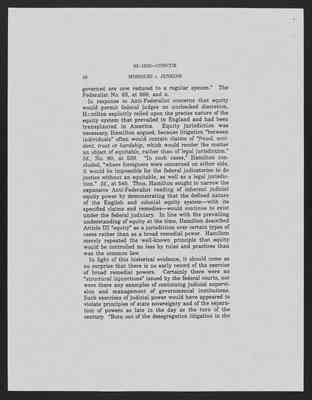

governed are now reduced to a regular system." The Federalist No. 83, at 569, and n.

In reponse to Anti-Federalist concerns that equity would permit federal judges an unchecked discretion, Hamilton explicitly relied upon the precise nature of the equity system that prevailed in England and had been transplanted in America. Equity jurisdiction was necessary, Hamilton argued, because litigation "between individuals" often would contain claims of "fraud, accident, trust or hardship, which would render the matter an object of equitable, rather than of legal jurisdiction." Id., No. 80, at 539. "In such cases," Hamilton concluded, "where foreigners were concerned on either side, it would be impossible for the federal judicatories to do justice without an equitable, as well as a legal jurisdiction." Id., at 540. Thus, Hamilton sought to narrow the expansive Anti-Federalist reading of inherent judicial equity power by demonstrating that the defined nature of the English and colonial equity system - with its specified claims and remedies - would continue to exist under the federal judiciary. In line with the prevailing understanding of equity at the time, Hamilton described Article III "equity" as a jurisdiction over certain types of cases rather than as a broad remedial power. Hamilton merely repeated the well-known principle that equity would be controlled no less by rules and practices than was the common law.

In light of this historical evidence, it should come as no surprise that there is no early record of the exercise of broad remedial powers. Certainly there were no "structural injunctions" issued by the federal courts, nor were there any examples of continuing judicial supervision and management of governmental institutions. Such exercises of judicial power would have appeared to violate principles of state sovereignty and of the separation of powers as late in the day as the turn of the century. "Born out of the desegregation litigation in the